Lucy Ives

Small Numbers Are Big

- Madame Bovary

- Hanne Darboven

- The Museum of the City of New York

- Renee Gladman + Renata Adler + Rachel Levitsky + Danielle Dutton + Lyn Hejinian + [...] = “ecstatic prose”

- Raymond Roussel

- Lists

- Annales School

- Awkwardness

- '90s minimalism

- ???

Madame Bovary

This is for me the quintessential modern work of art. I could go on and on about the intensity, purity, and ironic perfection of its descriptive passages, the calculation of its plot, the fascinating idiots populating it. What brings me back again and again is the cunning way in which Flaubert condemns his protagonist, locating her unsound core and the precise structure of her desires in the seedy leisure of her teenage years (she liked to look at pictures of lovers). You read, sensing the author’s distaste for this protagonist as well as his obvious deep identification with her needs, wishes. It is a creepy narrative, full of judiciously deployed hate, yet has never seemed misogynist to me. I don’t really care about dead celebrities, but if I could see/touch a living version of Gustave Flaubert I would be very happy.

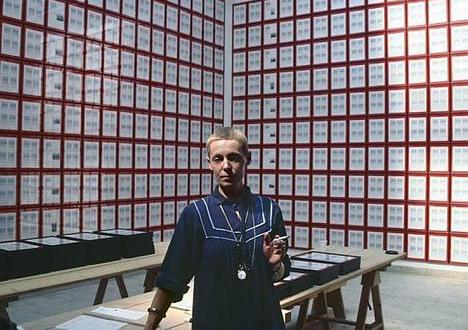

Hanne Darboven

This winter I was in a gallery and saw a small piece—a piece of paper, really—by Hanne Darboven. Suddenly the day was no longer lost. There was some writing on the paper, phrases and weird addition, and within the phrases the most striking word was Mondlicht, “moonlight” in German. There were also a lot of loops drawn on this piece of paper: “u”’s, as critics describe them. These are a serial display, daily marks, an abstract calendric kind of account. At the DIA Beacon they have her installation Cultural History, 1880–1983. This is all scary, powerful stuff.

The Museum of the City of New York

When I was a little kid in the late 1980s, the Museum of the City of New York, on 105th Street in Manhattan, had a small theater on the first floor that had been outfitted with a movie screen embedded in the back of a giant, artificial red apple. At a certain preordained times, the hour or half-hour, the apple would begin rotating, revealing this screen, and the lights would dim. A didactic film about the history of the land of New York City, beginning just before the appearance of Europeans, would play. At the end of this film the apple would rotate back, concealing the screen, and the lights would come up. They got rid of this apple, but I still like the museum. Upstairs there is a permanent display of dollhouses from the early twentieth century, including one made by the painter and poet, Florine Stettheimer. Currently there’s a show up of art collected by the painter Martin Wong. This is not a very big museum but it means a lot to me. The rotating apple meant a lot.

Renee Gladman + Renata Adler + Rachel Levitsky + Danielle Dutton + Lyn Hejinian + [...] = “ecstatic prose”

This is an idea about prose that I’ve so far only been able to name to myself—and for my own purposes. (I know, for example, that the term “New Narrative” exists and has its own life, but perhaps I mean something else.) I know that for me there is a connection to certain classic European novels, such as Wuthering Heights, somehow eccentrically for me, in my bizarre thinking, or Frankenstein. I suppose I am talking about the writing of women, but I do not mean the writing of women, exclusively. One could add in male authors I also name as my sources in this document. Anyway, this is an idea about prose that I’ve only been able to name, not exactly define. It’s difficult to define, since it takes various forms. A phrase from Lyn Hejinian’s The Language of Inquiry keeps occurring to me: “keeps its techniques bristling with perceptibility” (she writes this of Stein). This is prose thinking about the possibilities of prose; prose that makes no effort to hide this speculative thought.

Raymond Roussel

I recently made a map of all the events in Impressions of Africa. I have no idea what this book is about, and I don’t think anyone else does either. I’m very convinced by arguments that hold that Marcel Duchamp was brought to us/made possible by Raymond Roussel—though not very many people are making this argument. I like all of Roussel’s long poems and novels; they were written by a lonely and very energetic person whose life was probably sometimes made worse by the amount of money he had and who unfortunately did not live very long, and I think that when (if) I am an old person I will spend a lot of time making diagrams of these poems and novels and trying to understand how they function.

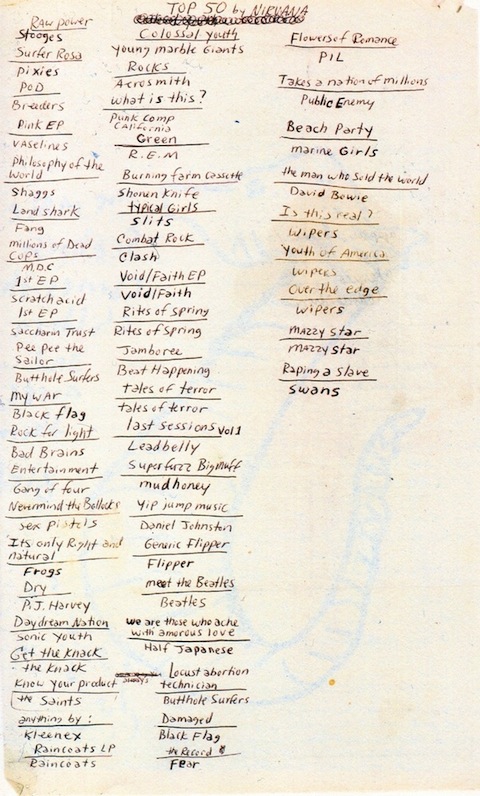

Lists

I am not sure how I first became drawn to lists. It may have something to do with a certain teaching moment of my early twenties: I was informed by an instructor that the difference between a poem and [anything else] is, a poem “is not a list.” I guess in this account a contemporary poem is a short piece of writing with some sort of special internal coherence. (In light of our present non-dependence on prosody and rhyme to provide this coherence I am not sure where that comes from, but I digress.) Around this time I read for the first time the definitive medieval novel about taste, The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, which is full of very good lists: “Things That Have Lost Their Power,” “Rare Things,” “Annoying Things,” “Splendid Things,” etc. I started to think that a lot of sentences and phrases could be vastly improved by being included in a list. The list’s extra dry format never gets old, somehow. And the sound of counting (if you choose to number your list) is a really pleasant and classic sound.

Annales School

I wish I knew more about the Annales School. On some level I keep liking not knowing that much so that I can continue to imagine that this is a way of writing history that takes as a starting point the idea that objects are capable of making arguments. If I had all the time in the world this is what I would read almost exclusively. I read a number of books by Roger Chartier this winter but not enough.

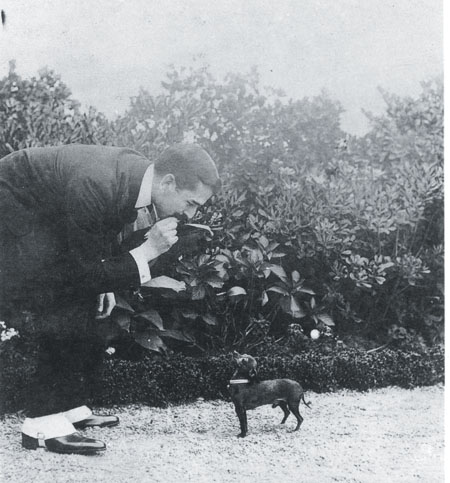

Awkwardness

I have a tendency to overthink things and also to make things up. Like anyone, I can certainly appear strange in public. A number of people have recently told me that every time they see me I look different, as in, every time they see me I look different, to the point of near unrecognizability. Someone said, “[Lucy is] like a spy.” It’s not my intention to deceive anyone. I think of this as a kind of awkwardness, a hiding in plain sight or failure to appear, something it would be better not to have a tendency to do. All the same, and in spite of better intentions, I find myself inspired by the awkwardness I see in others, as when Rousseau is knocked down by a dog or John Berryman talks about a sheep that wrote his poem. Awkwardness comes close to the tendency to be pathetic, but with a flatter, less inquiring charm. I would much rather see someone pretend to be awkward than see someone pretend to be pathetic (since someone pretending to be pathetic really is, whereas awkwardness can be successfully faked). I like lulls in conversation and illegible affect and bluntness and shyness and springtime.

'90s minimalism

There is a thing about 1990s fashion that causes it to affect us in the way that it does/has, retroactively, and that thing is something that I call “’90s minimalism.” ’90s minimalism is the insoluble center of ‘90s anything. It looks like Rei Kawakubo and it looks J-P Gaultier and it even looks like heinous Marc Jacobs for Perry Ellis or any kind of Calvin Klein underpants. It looks like the way Calvin Klein looks when it becomes “CK.” It is Gwyneth Paltrow with no eyebrows in a formal crop top and the desire to wear lots of square-toed shoes. It is neutral. It is progressive rather than modern. It adores wet-looking hair and androgyny and is somehow related to the rise of the rave. It is the first year of Wired. It is the next three years of Wired. It is a low of popular taste, much like the 1970s, and, like many downers, is seen as eminently suitable for public consumption. It is oddly one of—if not the—least subversive aesthetic(s) produced during the twentieth century in the U.S.

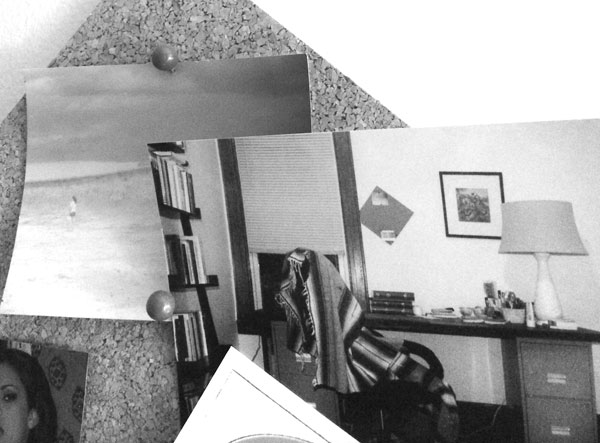

???

(So here is a list of everything that is on my desk right now, until I got tired of typing:)

A stapler, two failed/unpublished novels in manuscript, a kindle in a felt sleeve, a copy of The Westwind Review, The Sore Throat by Aaron Kunin, An Essay on the Original of Literature by Daniel Defoe, A Year in the Dark by Renata Adler, Écrits sur l’art by Huysmans, a white rock, three different chapsticks, two teacups that belonged to my grandmother, a bottle of Waterman blue-black ink, three unopened packages of unlined index cards, clay planter containing pens and pencils, small blue stuffed bear, bills, comb, For Want and Sound by Melissa Buzzeo, Adam’s Summer Purgatory by Adam Humphreys, The Emergence of Social Space by Kristin Ross, Politiques de l’amitié by Jacques Derrida, a flat gray rock, a wooden building block I drew on when I was four, The Crystal Lithium by James Schuyler, Our Aesthetic Categories by Sianne Ngai, The Shirt Weapon by Brandon Downing, Don Quixote by Kathy Acker, François Laruelle’s Les philosophies de la différence, Darren Bader’s Life As a Readymade, Olivetti Praxis 43 typewriter, MacBook Air, La route antique des hommes pervers by René Girard, Ramus, Method, & the Decay of Dialogue by Walter Ong, Writings of Marcel Duchamp by Marcel Duchamp, Sorting Facts: or, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Marker by Susan Howe, The American Poetry Wax Museum by Jed Rasula, [etc.]

Lucy Ives

Lucy Ives is most recently the author of Orange Roses (Ahsahta, 2013), a collection of poetry and essays, and nineties (Tea Party Republicans, 2013), a novel about a decade. Her work has appeared in BOMB, Conjunctions, Fence, The Huffington Post, n+1, Ploughshares, and other journals. A deputy editor at Triple Canopy, she is co-editor of Corrected Slogans: Reading and Writing Conceptualism, published by Triple Canopy and the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. With Triple Canopy, she participated as an artist in the 2014 Whitney Biennial.