Naomi Washer

Mysterious Objects

- Reading Koestenbaum

- Reading Zurn

- Marina Tsvetaeva & Boris Pasternak: Cor / respon / dance

- Sacred Harp

- Sam Amidon, “As I Roved Out”

- Queens for a Day

- DV8, “The Cost of Living”

- The Diary of Izumi Shikibu

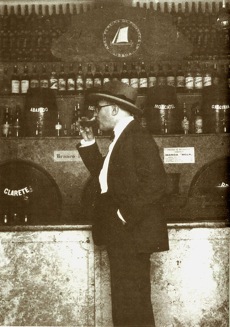

- Bruno Schulz

- Fernando Pessoa

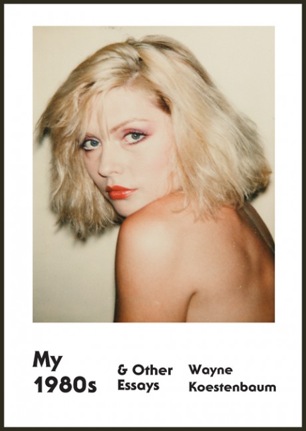

Reading Koestenbaum

I’m crushing hard on Wayne Koestenbaum. If a crush is a fall headfirst down a canyon you may never climb out of, then yes, I have a major crush on Wayne Koestenbaum and I do not want to recover. This is not about the man but the writing, the space between the author and text. In matters of literary criticism, I am interesting in closing that space. I write in the margins of Koestenbaum; I feel compelled. As if I didn’t know what reading was before, though I know what desire is. Koestenbaum plays dirty; his essays are the high school summer nights we played Never Have I Ever in each other’s backyards. (“I appreciate the back room, the backyard, the backstreet, the back door—the prior meaning, the obscured scene, the oblique entrance to revelation.”—“The Rape of Rusty", My 1980’s). I blush reading Koestenbaum because I know the act of writing is erotic for him. I’m realizing it is for me, too. By good writing, I want to be fucked. If a writer is not trying to fuck me with their words, I feel half-fucked. The essay repressed: a tease. Even his name—Koestenbaum—I cup it in my hands—feels kinesthetic. And I am a kinesthetic learner.

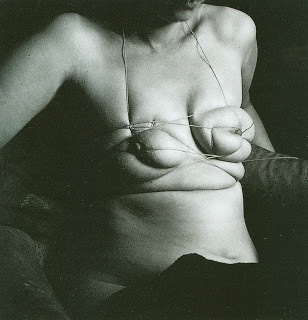

Reading Zurn

is disturbing. It is uneasy, unsettling. A little girl as sadist and masochist. Despite the third person (the author) and the lack of name (perceived identity) of the protagonist/”narrator” (there exists a distinct separation) one aligns oneself with her, one identifies, one feels the strings tightening and cutting into the flesh across the stomach and breasts. One understands that space which she accesses between things and words and one, yes, feels painfully and destructively, that rupture. What Unica Zurn shows us is that to write is to submit to all the painful pleasures associated with life. It is not a high and lofty pursuit but rather a dark, slim passage through which the writer slips, now in, now out, now again in, and from which the writer sadistically seeks to never leave.

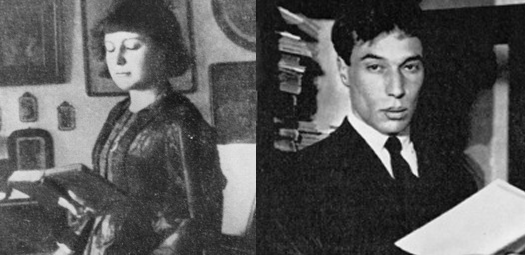

Marina Tsvetaeva & Boris Pasternak: Cor / respon / dance

Pasternak to Tsvetaeva:

“I felt the urge to talk to you—and immediately I was aware of the difference. It was as if the wind had ruffled my hair. I could not write to you. I wished to go outside to see what one poet’s thinking of another had done to the air and sky.”

Tsvetaeva to Pasternak:

“…and I greeted you with my whole body, and with the wind in my face. Back at the house, everyone was still asleep. I stopped and lifted my head to see you. Thus I live in you, morning and evening, getting up in you, lying down in you.”

Sacred Harp

https://www.youtube.com/embed/m0kbrsu1Bhs

Teach me some melodious sonnet

Sung by flaming tongues above

Praise the mount, O fix me on it

Mount of God’s unchanging love

Sam Amidon, “As I Roved Out”

https://www.youtube.com/embed/KCHcH2xCBlE

When you’re the son of musicians and you’ve been playing the fiddle traditional Irish style since the age of three, and it’s the mid-2000’s, you go to New York City because that’s where musicians live these days, and you jam out with other musicians because you don’t know what you’re supposed to be playing and why. Because you want to make a life out of music like your parents did, but it’s different these days, so you make your money playing traditional Irish fiddle, and you play it so much you can play it for hours, and you know all the names of the songs, and it’s the closest thing you’ll get to being an expert in anything. And maybe you’re a little sad, too, because you don’t know why you’re in New York City, but you just tell yourself it’s a short life of trouble, few more days, few more days of woe. You start playing with these other young musicians who are more experimental, a little space-y, and that atmosphere starts to make its way into your bloodstream and your banjo. You see that everyone who’s getting anywhere is called something like a singer-songwriter, and you don’t really think that’s what you are, but you’ve got nothing else to do so you start trying to be a singer-songwriter and you start trying to write songs. You get some pretty good guitar parts out, but you’ve got no head for lyrics, because when you were a real little kid there wasn’t any music like that in your house. And you live in New York City now, and there aren’t any silent woods to rove out into like there were in Brattleboro, but you start realizing there are all these words already stuck in your head, and the words have a melody_—what is it banjo?—_and the words are old and you don’t know who wrote them, but that’s okay, because somebody somewhere ages ago did, and the thing is, it’s okay for anyone to sing them, so you go ahead and start pulling them up out from wherever they came, and maybe dusting them off a little, and wrapping them up inside your guitar parts, and you start singing them.

Queens for a Day

https://www.youtube.com/embed/yUh0ZbVYlDA

This is my favorite dance film I have ever seen. I show it to my students in first-year writing composition classes. I have them write a little response while they’re watching. I read them later at home and every single one says, “WHAT IN THE HELL ARE THEY DOING. I don’t think rolling down a hill is dance???”

DV8, “The Cost of Living”

http://www.youtube.com/embed/0ZTMyWt50kk

They come, most often, in disguise

They come in church, in the sanctuary, on early Sunday mornings.

They come in your broken leg.

They come in you not being able to run because of your broken leg.

They come in all your thoughts while you’re not running because of your broken leg.

They come in all the questions that result from the thoughts you’re having while you’re not running because of your broken leg.

They come in how you ask yourself to change because of all the thoughts you’re having while you’re not running because of your broken leg.

They come in wondering why you never questioned yourself so much when you were running because you didn’t have a broken leg.

They come in the realization that you never thought you would ever break your leg and now that you have broken your leg everything has changed.

They come in the new way you will run after you’ve rested and done all of that thinking and the doctor says yes, now you can run, because you have a new un-broken leg.

They come wrapped in a bundle.

They come in hospitals with mothers, from mothers.

They come from my mother’s mouth, the word at least, the shape of it and sound: bless ‘er heart.

I love the way my mother says it, from the South.

I love the way my mother gives me one by saying it.

I love the way she gives them all away so often.

The Diary of Izumi Shikibu

“How easily she had given a more interesting turn to his thoughts. How attractive she was. If only there were some way of getting her near at hand to be able to enjoy such exchanges all the time.”

yet there is a fear in having each other closer, a train or bus ride way, walking distance, opening the door, turning the corner…if I can be so easily found, so easily seen, at unexpected times, in the broad fluorescent light of a hallway, then I cannot design, I cannot pause to gather and present. “Her letter arrived at just that moment—she must have been startled by the extraordinary whiteness of the frost.”

cooking soup one morning at the shop, someone nearby spoke some words that reminded me of him, of a conversation we had had the evening before, and I pulled my phone out of my pocket and turned it on to write him, but when I turned it on I found that he had already written me, had already sent me a poem, a poem for me, which is different than a poem about me, though it seemed to be.

“When the messenger came with the answer, she opened it with a twinge of disappointment that he had replied too fast to have entered completely into her feelings.”

Bruno Schulz

How do we arrive at certain images in childhood? And how do we work with those images? How does the personal essayist work with them differently than would the fiction writer or poet? The personal essayist (and here I do mean the personal essay as genre and not the essay) attempts to capture a story, the narrative of a memory as it happened, and apply a reflective moral to the tale. So it is a different impulse altogether to want to make art out of images and this is perhaps the only reason The Street of Crocodiles is marketed and read as fiction, to give readers a window into the magic of childhood, the mythology of family, without those readers complaining that Schulz’s father could not really have turned into a cockroach, that actually he suffered a long illness that caused him to retreat into himself, to be confined to only the house, to thus become smaller. But how is this not believable? I recall the man I dated once who, when we met, was as free and open as a child, then through the general difficulties of life became smaller, retreated into himself, only emerged every now and again to quickly snap at my heels and then scuttle away, and so I believed him to have transformed into a crab, and ultimately left him beneath the rock under which he had decided to crawl.

Fernando Pessoa

I am reading and analyzing a specific book by a specific author. But I am also reading them, as I hope my readers attempt to read me, for the relationship between a writer and a writer’s text is not a separation between nor an illustration of but rather the means through which the writer comes to exist, and so, remain.

One can pick up The Book of Disquiet and begin and pause and begin again at any place between. Pessoa does not require chronology in order to be understand. He is not a chronological person because he is not only one, which I think we would all do well to apply to ourselves at least a little. Picking up Pessoa again and again is therefore not a beginning but yet another encounter, another chance to meet, to see, to attempt to know or understand yet with the acceptance that that will never be achieved in full, and why would one want it to be? Why would one ever stop wanting to know?

Naomi Washer

Naomi Washer is the Editor-in-Chief of Ghost Proposal. Her essays, poems and Cambodian translations have appeared and are forthcoming in South Loop Review, the birds we piled loosely, Ampersand Review, Skydeer Helpking and St. Petersburg Review. She is an MFA Candidate in Nonfiction at Columbia College Chicago where she teaches first-year composition.