Ben Pease

Misogynist Gods

- Ambivalence and Claude Lorrain's Aeneas's Farewell to Dido in Carthage.

- Detail from Guernico's Death of Dido as a snapchat

- From Book VI, The World Below, The Aeneid

- Master of One (at a time)

- Freedom with (or without) Disaster

- From The Laws of Change by Jack M. Balkin

- "Fauna of Mirrors," in Jorge Luis Borges' The Book of Imaginary Beings

- Infinite Earths, Infinite Crises

- Deaths of the Flash

- Parallel Universes and the Imagination in Neil Stephenson's Anathem

Ambivalence and Claude Lorrain's Aeneas's Farewell to Dido in Carthage.

I noticed the favored epithet for Aeneas was "duty-bound." I initially thought it meant he was bound to a moral code (which may be true), but he is bound more to the will of the gods, who knew they couldn't prevent him from reaching Italy but would make him suffer along the way: rough seas, men overboard, short respites, and sacrificed women. This last point seems nothing but a cheap device to create complexity in a male character via the death of female love interests.

This has happened twice for Aeneas so far in my reading: first, he loses track of his wife Creusa during the escape from Troy, and she dies. Maybe I'm biased having just gotten married, but if everything's going to shit, I'm putting all my energy into getting my loved ones out alive. If that wasn't enough, he gets all cozy with Dido but ditches her because the gods say so, leading to her suicide. I was thinking about this when I found this painting. The Web Gallery of Art notes that "Claude had a relative lack of interest in his subject-matter. [ . . .] Unlike Poussin, who tried to imitate his source in as accurate a manner as possible, Claude used the poetry as a source of general inspiration for his pictures, which remained landscapes first and foremost." Somehow this painting's ambivalence towards the specificities of The Aeneid is a righteously-indignant analogue to Virgil's ambivalence towards the major women in his work.

Detail from Guernico's Death of Dido as a snapchat

Dido deserved better. She is basically the anti-Miss Havisham, who (instead of letting the loss of her love bring her down) makes a better life for herself and her people. She would have continued to have her shit together if not for Aeneas and his wake of angry gods. It’s almost like a deus ex machina that artificially extends the story instead of resolving it. How awesome would a kingdom ruled by Aeneas and Dido have been? Nope. Sorry. The story has to end later!

I don't even use Snapchat, but I put this together because I wanted to make light of Dido’s unjust end. Dido’s sister or whoever looks like she’s trying to convince her that not every man is like her back-stabbing brother or “duty-bound” Aeneas, but Dido just thrusts the sword in further and asks for some fire. Dido wanted life, a life of just being a woman who loved and provided for her people, but the gods wanted her to have it only long enough so it would hurt the most when they took it away.

From Book VI, The World Below, The Aeneid

Here in Book six, not only is Aeneas going to run into Dido as he goes through the land of the dead, but he also just has to make her feel bad along the way. When Aeneas' entreaties for forgiveness are met only with savage glares, it seems like I'm supposed to feel sympathy for Aeneas and all that he must sacrifice for Italy. Dido is completely justified here, and I don't get why she isn't more thrilled to be back with her husband! Either Virgil didn't care or want to give her that satisfaction.

What's also strange is that "Aeneas still gazed after her in tears, / Shaken by her ill fate and pitying her." Aeneas is displaying some full-blown compartmentalization whilst denying any responsibility. Ill Fate? How about Ill Aeneas? He's put the blame on the gods, and even though their love SHUT CARTHAGE DOWN, he seems surprised she would react so wildly to his departure. The answer to his question, “Am I someone to flee from?” is a resounding yes! Stay the fuck away from Aeneas if you’re a woman from anywhere but Italy! If only she stuck to her original vow and didn't fall for another man [1....](href="#_ftn1" name="_ftnref1")

[1](href="#_ftnref1" name="_ftn1") Oh that's right, Venus conspired with Cupid and forced Dido to fall in love with Aeneas.

Master of One (at a time)

I watched Adaptation again the other night both for myself and to see if I could show it to my Composition I class as part of a two-movie section that ends with a compare/contrast paper. I get a lot of anxiety about sitting through awkward-as-hell moments as the "leader" of a classroom, and there are some pathetic masturbation scenes with Nic Cage's Charlie Kaufman to contend with. I think I can put up with it in this case because the theme of inspiration is so strong. What I admire so much about Laroche's (Chris Cooper) sense of inspiration is that it is both complete and temporary. Whether it’s turtles or 19th century Dutch mirrors or orchids, Laroche devotes himself to that field utterly, but once his immense curiosity has been satisfied, he moves on. I find it often the same with writing: a subject or person is sometimes poured over until exhausted and used in our writing with the hope that however we were uniquely enchanted might be understood by others.

Freedom with (or without) Disaster

Laroche finds himself in a situation not too different from Aeneas in that the death of loved ones affects his character: he pulls out of his driveway and a truck smashes into his car, killing his mother and uncle. It is a surprise to see that the wife survives, and what distinguishes this moment from the senseless female deaths in The Aeneid is that it also builds character and complexity for the women. Furthermore, where Aeneas becomes more noble by weathering the deaths of his wife and then lover, Laroche is literally and emotionally torn apart. He can't replace the teeth he lost in the accident just as he can't bring back his mother, uncle or marriage. Unlike The Aeneid, this situation becomes an accidental boon for Laroche's ex, who gains her freedom, and for Orlean (Meryl Streep), who realises that freedom is possible even if a readily available disaster doesn't offer itself as an excuse.

From The Laws of Change by Jack M. Balkin

I was waiting for Sasha Fletcher to finish his laundry so we could play some video games together, and I downloaded a new translation of the I-Ching and had a beer. I remember reading a commentary-heavy version in the library at Emerson College when I was an undergrad. I was dozing off as I read it, slightly confused but also exhausted because I had done a 6-10am radio shift that morning. This would have been a completely unmemorable experience except someone tapped me on the shoulder and informed me that the library wasn’t a place for sleeping. This person didn’t work in the library. Was I snoring? Were they hitting on me? I was too tired to understand the subtext of this interaction, but now I realize that a dramatization of the I-Ching had just taken place before my eyes. In terms of “making commitments and living up to them,” I had completely failed.

I like this definition of modesty because it requires that one be proactive. It’s not simply how humble we demand our celebrities to be off-screen. Instead, it makes dedication to a worthy task the most venerable kind of action, and it’s refreshing to read about the ego being involved in a productive and positive way. I find that in dark times, which we are no doubt in the middle of, I return to texts that deal with essential principles so that I might fortify myself and try to remain a decent human being.

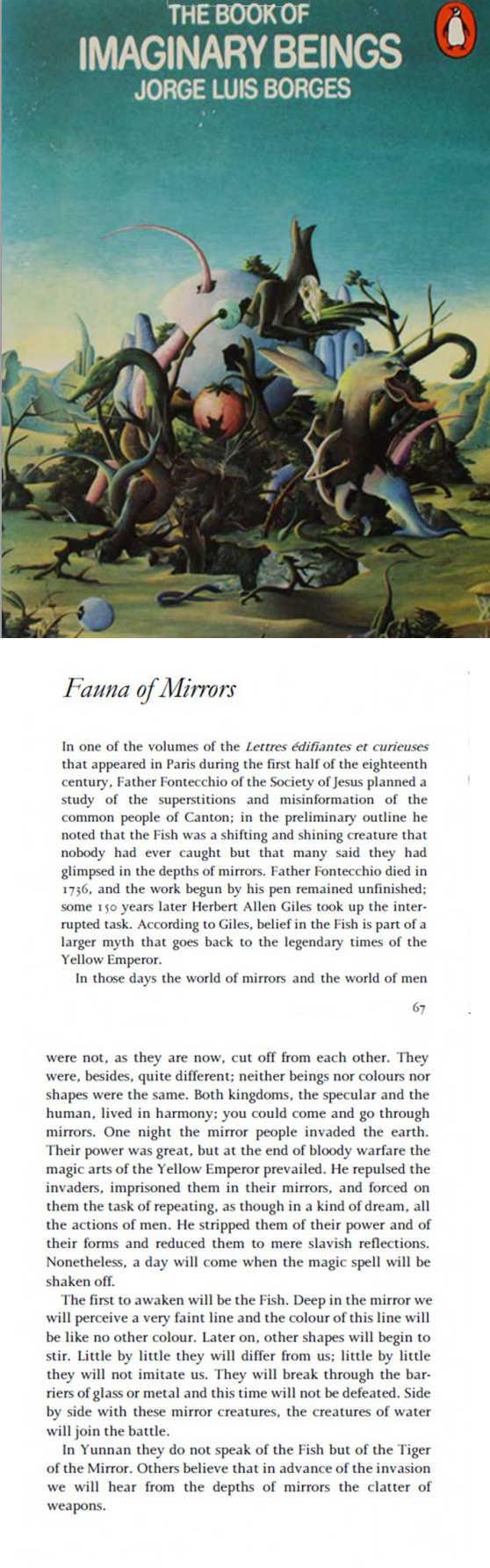

"Fauna of Mirrors," in Jorge Luis Borges' The Book of Imaginary Beings

Borges was terrified of mirrors because he feared the duplicate might take over—the movie Multiplicity is basically his worst nightmare realized. I love myths that recontextualize everyday things and simultaneously define the thing and add new, highly imaginative elements. I became obsessed with mirrors once I noticed our cat sitting in front of a mirror and looking into the reflected room as if it were real while not giving any credence to its reflected self. Mirrors have become overused all over the place, like in horror movies where broken shards will reflect different aspects of a psychotic person’s personality, so finding new ways to interact with a common object is always invigorating.

The cat inspired me to find other literary counterparts, which reminds me of a Joyce Carol Oates quote from the anthology I teach from where she advises to avoid too much research, in her case related to a news clipping that inspired one of her stories. Let the imagination run with the details that fascinated you in the first place. I tend to go the other way, read about a topic until I can’t stand it anymore, but when I return to write about it, I use what seems like very little of what I’ve read. Internally, however, I think all of these competing sources quietly shape what comes out on in the end.

Infinite Earths, Infinite Crises

Infinite Crisis: Fight for the Multiverse, 2014

I read a decent number of comics, but I almost didn’t include some here until I figured out how to take screenshots on my Nook. I for the most part only read DC titles (mainly Batman, Justice League, all the Green Lanterns), but the crossover stories, where all the heroes are involved and the stakes are set as high as possible, are always enjoyable for the ridiculous action and twists and turns.

I’m particularly drawn to the DC crossovers because they deal with conflicts where the fate of all (be it an infinite amount or 52 or however many) parallel universes hang in the balance. I remember reading a while back (probably on Wikipedia) that the initial crossover, Crisis of Infinite Earths, was created because there were too many parallel universes/storylines, and the crisis was a means to thin the herd. Thinking back on this makes me want to re-read Dana Ward’s Crisis of Infinite Worlds, and while his interaction with the series is limited (he walks by a comics store and initially misreads the title), it leads to a series of wonderful musings and gets at the imaginative nature of the comic form itself.

Here are truncated shots from the opening of the original Crisis of Infinite Earths and the new digitial-only Infinite Crisis: Fight for the Multiverse. Although it seems easy to retell/redo a story that isn’t even that old, it also has the feel of a myth being rewritten to match the times.

Deaths of the Flash

Crisis of Infinite Earths, 1985

Zero Hour, 1994

Comics are addicting as hell. It’s great when you begin because you can binge on back issues to your heart’s content. Then there’s the tie-in factor: for example, you’re reading Justice League, Batman shows up and seems somehow broodier than usual. There’s one cell where he says something like, “I was in upper Mongolia looking for the stolen corpse of my son,” and without a blink the Justice League story continues on. Before you know it, you’ve read five years’ worth of Batman comics because of that one off-hand remark.

Reading Zero Hour recently, I was thinking about how the comics speak to and respond to each other over the ages. It’s another addicting element that gets you to re-read old stories and think about the relationships. In the first image above, the Barry Allen Flash runs himself into the ground in order to destroy a cannon that can obliterate worlds. In the second, the Wally West Flash attempts to reach “ultimate speed” and destroy a ball of entropy that’s consuming the universe. There is a satisfying combination of repetition and variation in the trope: The Flash must run himself into non-existence to save the world/universe, his uniform remains, but success is not always guaranteed. In both cases, of course, The Flash doesn’t really die but comes back at key points in other crossovers. There’s even that single frame in Zero Hour which alludes to the original death.

Parallel Universes and the Imagination in Neil Stephenson's Anathem

Neil Stephenson really knows how to mix and match. In Snow Crash he combines hacking, virtual reality, Eve, linguistics and the Sumerian Language, and here in Anathem he brings together philosophy, ascetic living and parallel universes. I actually read Snow Crash much more recently, but I returned to this passage because it’s got a lot to do with what I’ve been thinking about. Stephenson is in line in many ways with DC comics when it comes to parallel universes but takes a much more theoretical approach. This is the kind of topic where you can step into the deep waters of quantum physics and be lost immediately. Thankfully, Stephenson toes the line between the technical and the understandable, but what really draws me to this passage is its unique take on how the mind works. It brings together what at first seem like competing theories: “everything has been done before” and “anything is possible” become “your brain can pluck ideas, which already exist, out of an infinite plentitude of parallel universes.” The allegory of the cave made real to an exponential degree. The thing I enjoy the most out of this passage is its unapologetic wish fulfillment-esque notion that humanity, through our brains, has an intimate connection with the universe at large.

Ben Pease

Ben Pease is the editor of Monk Books and a member of The Ruth Stone Foundation. His first collection of poems, CHATEAU WICHMAN, is forthcoming from Big Lucks. His work has appeared in BOMBLOG, jubilat, Salt Hill, and SUPERMACHINE, among others.