Brandon Kreitler

from The Travel Letters of X

A knife separates a pear in sink-water

like a word insisting on its difference from the world

as such. The town children have not burned through

whatever pleasure lies in banging on shutters and running

through the square.

The old man tells me they sleep most of the day

after having said that though he is old the era still belongs to him.

The sea holds the light of the town extending like layered cake from the shore.

This morning she said how are you and I was too many ways to answer.

It made sense then that days are measured like this, by the sun and the times when toast is served. I danced

before breakfast but soon became tired, as though

I were trying to convince myself of something

––to prove by means other than a bloodless cut of fruit in water,

in a bare flat, where the strata of light and heat are just light and heat

and the streets are peopled always.

I speak like a tourist.

We walked to the mouth of the river, to the edge of a sea still receding.

Sometimes at night I sit in the kitchen and arrange sugar cubes

on the windowsill. I say

here is fire, here is wind.

The only desire sustained in speaking is for a purer speech.

The sea sinks and returns to itself. A child’s game: here and gone.

We spoke of the boats landed in the wide basin.

I wanted an object to stand for what I wanted.

I thought I would approach you in the slip of words.

The old man said his first memories were of light and death,

which makes no sense except that light

through a church window would take the shape of argument

only light can further.

An empty conduit driving itself into the space emptiness fills.

One wonders how many things there are about which to speak.

I was scrawling maps across your eyelids. The song on the radio kept

bleeding into itself like a feedback loop, piling

like a mountain, and it seemed every sound a moment could bend for

was filling the room.

In my dream the marionettes were on fire.

There was no backdrop. Rather a hole in the theater wall staging

the selfsame city.

The usher was useless. He kept talking about shuttlecocks.

You were an empty body.

The motion of a shutter. Your name like a word eating itself, your bones

beside

the bed.

Think of water,

the slippage in plain speech.

Witness the insertion of the mirror

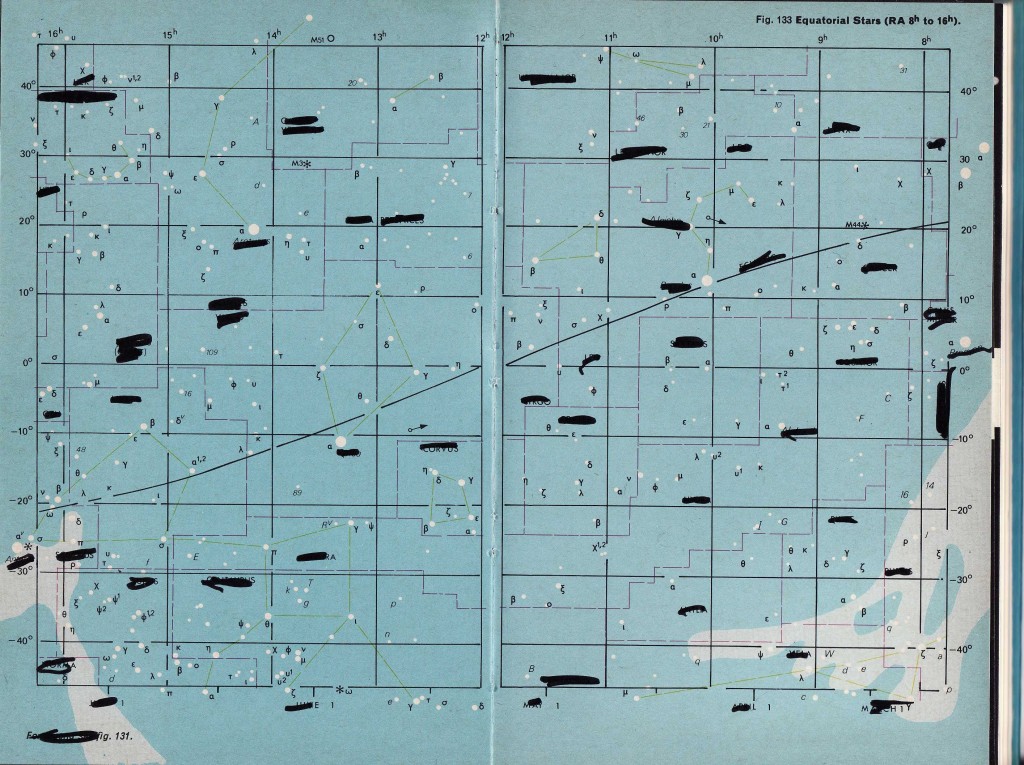

––then the mirror only. “The coordinates of the apparent star

having shifted incalculably despite the extension of its light.”

The body

of a bird cast scattershot in the light slipping through the window, slipping through

the pictured facts of the city.

The schema of the coast

and the relent of its pink light. Boats in harbor entropy.

We’ve learned much––read every word of the safety manual: to know

the sensation of drowning is only to know you’ve not drowned.

The fact of light on a drawn curtain.

Hands clasping the wood grain of the breakfast table. The names

of rivers running into each other. Lovers with a blanket strewn on the deck of a carousel.

Stars like index of the words we’ve yet to learn.

And the part you always forget is that

it’s actually happening. But nothing gives itself up.

Nothing breaks from its own spectacle. The whirl of light, the bend in the light.

How little I’ve said of my day.

The clatter of the ceiling fan. The change on the dresser.

The gradient flow of rainwater in the streets, themselves the slant-solder of memory.

The fissures in the bed sheets. The fissures we draw to make the space between us

uninhabitable. It’s not that it hasn’t

all been said before, it just hasn’t

been said in a way that has anything to do with us.

Brandon Kreitler

Brandon Kreitler’s poems have appeared in Conjunctions, Boston Review, Indiana Review, Maggy, Cutbank, DIAGRAM, Omniverse, Vanitas, Stonecutter, West Branch, Verse Daily, Company Journal, and Atlas Review among other journals. A chapbook, Dusking, is out from Argos Books. He was a winner of the 2010 Discovery / “Boston Review” award and lives in New York City.