Danielle Vogel

Edges & Fray (gathered for Narrative & Nest)

- Habitation

- Solidity & Sound

- Gestation

- Roof & Cup

- Tension & Suspension

- Encounter

- Fray

- Debris

- Weave

- Archive

Habitation

A nest’s helixical nature, suspended in-tension. Silence in relation to making a trace. Listen.

I had not yet written a book. I was a woman who had come to language early on.

A bird leaves to return, leaves, returns again. Weaves a thing. Presses its breast against the circle. Inverts itself against the weave. No, the weave becomes its inversion. A nest. A dwelling-shape that harbors. This paragraph, can you rest here?

Solidity & Sound

For all creatures, the most primal form of shelter is a hollow: a simple cavity dug into earth, a depression in the sand, the carved out alcove of a tree. For a writer, the most primal form of shelter is a word. All words are terranean. Each, beginning deep below its own surface.

Gestation

This book began as a series of ceramic vessels. It began as I walked, as I stood. It began during a late autumn snow. All around me, a harvested color: the broad foothills, coarsely tasseled grass, low cacti, tan cows huddled against the cold. It began on a rough tract of land as I watched over a pit kiln built of red earth and cow dung. Below the dung roof, small hand-built pots turned black and copper as they fired over the hours. And as they fired, I stood thinking about my own form—its heritage, its present moment, how I had come to be there.

Roof & Cup

A bird’s nest is a physical geometry of its thinking. It is a unified and symbiotic shape of its circumstance, a mending of its body language and place. All nests are adapted for habitat, for desire. It is the synergetic relationships between the built, the place from which the thing was built, and the builder that interests me. How all—through communion and conversation—enable life.

When I look at a nest, I see narrative. I see a residence, a thing to be read and inhabited. I look to nests to better understand my own integration.

Tension & Suspension

We come to language as architects of relation, but sentences are not secure. We take them up as planks and make unstable geometries. A book arrives in threads—both as it is read and written. And those threads—depending upon who is reading and writing—are plaited into distinct shapes. Within a home or book we huddle up to ourselves, but what of the thing into which we are huddled: the refuge. What of its composition? We intersect it with our thinking, with our having lived and thought within it.

Encounter

We are compositions of how we perceive and remember. But what is the record of a body that so often does not recognize its own materiality? What is language’s relationship to disembodiment and communion?

When we enter a book, we enter the thinking of another. We—the reader and writer—become temporarily amalgamated through language’s ability to bond, to create momentary enclosures. Writing and reading extends the boundaries of a body by creating a common somatic field. I come to language because I want to bridge myself out of my own disorientation, I want to bridge to the world and to an other. The wholeness that reading engenders is not hermetic, but extensive, built out of a series of interlacing fragments within which we meet a larger, more complete version of ourselves.

Fray

Our nervous systems respond. We are contained, but always practicing diffusion.

Debris

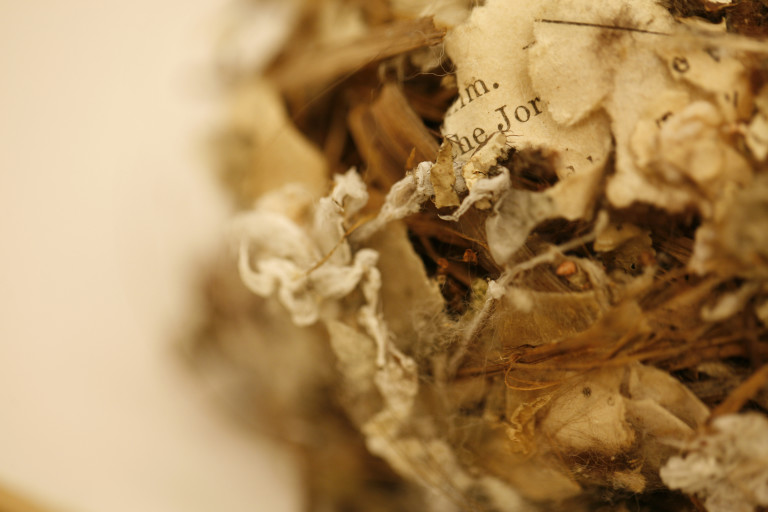

Each bird is an archivist of debris, always in a constant state of accretion. The microcosms of a nest: its accrual, collected, woven, incubated, and then in some cases, abandoned—has helped me to better understand language and intimacy, architecture, our abilities—as builders—to story and spell.

Weave

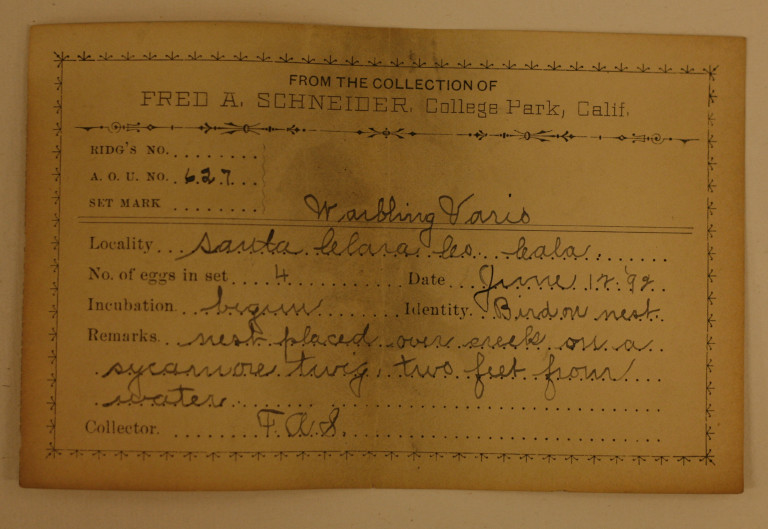

We read debris and make seemingly complete shapes. What we experience is a series of fragments and the ethereal impulse of an entirety. Nests have taught me about the minuscule that haunts toward the whole. Books and nests are archives of a time and place: what surrounds them, what was harvested for their form, who lived there, when. An entirety comes to life: the red string of the mockingbird nest, the newspaper in the warbler’s, the woman who lifted the woodpecker’s nest from the husk of a saguaro.

Archive

In the stacks at the museum, some nests have been reduced to filaments and dirt. Strands of loam. Archivist string hooping what used to be contoured. Hay, horsehair, lichen, birch bark, matches, and small pocked bones. These nests tell me of severment and bisection. A fragmented space. I enter to archive.

Danielle Vogel

Danielle Vogel is an artist and writer who grew up on the south shore of Long Island. She is the author of Between Grammars (Noemi Press 2015), the artist book _Narrative & Nest _(Abecedarian Gallery 2012) and lit (Dancing Girl Press 2008) and has exhibited her work most recently at RISD Museum, The University of Arizona’s Poetry Center, and Abecedarian Gallery. Currently, she is a visiting writer teaching at Brown and Wesleyan Universities. Danielle is at work on a book of lyric essays titled Narrative & Nest. These are some of her notes toward that future book space.