Davy Knittle

Simple Machines

- “My Star, My Sun, My Other Self”

- Untitled [Purple, White and Red], 1953

- “it’s one of those / days I want to get / along with everyone / and don’t and / don’t know why” – Frank Sherlock and CA Conrad

- The style’s deep even when we fall asleep / dreaming of the usual: a rap beat - Charizma

- “My poem sequence is to reinstate (restate) experiencing in space, the mind/eye making estimations/approximations as concepts that are the same as their being in space” – Leslie Scalapino

- Simple Machines

- Model Cities

- The Cook’s Companion

- “Icarus, a long time ago, broke his limbs.” – Le Corbusier

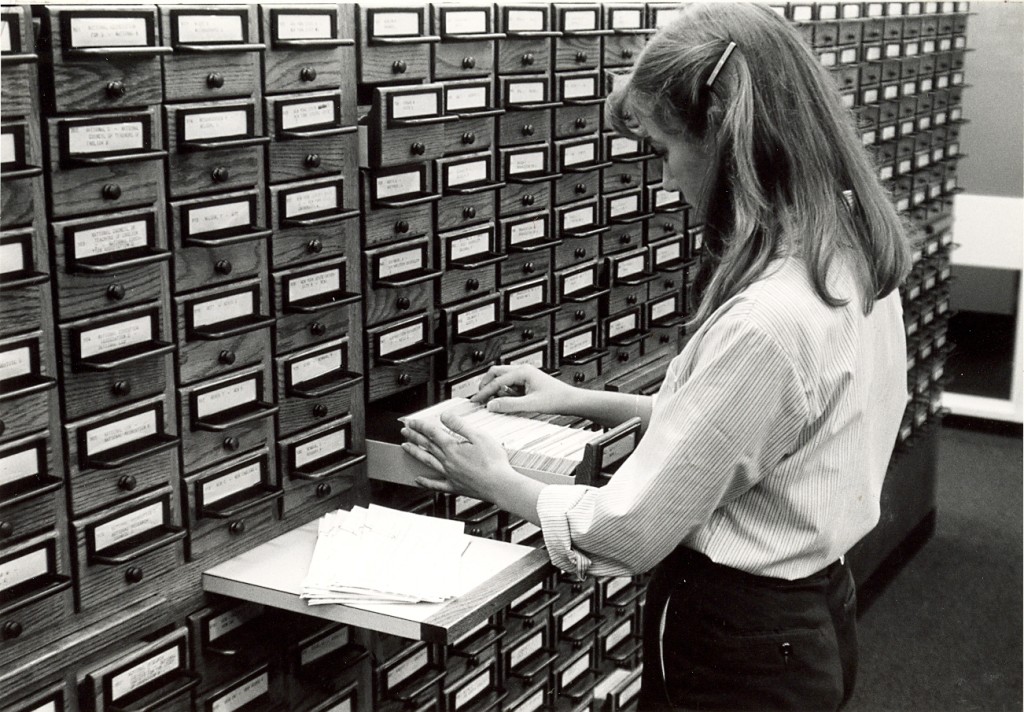

- Catalogue Impulse

“My Star, My Sun, My Other Self”

In figuring out what poems can do, my undergraduate students have become excited about reading for differentials in scale. We read James Schuyler’s “Letter Poem #3” and they’re thrilled with: “So many / galaxies and you my / bright particular / my star.” I try to work “my star” into a poem several times, and can’t decide what to do with the union of big and small, whether to resolve to the galactic, or the tiny.

In the same few weeks, Sophie and I start a reading series. Our second reading brings forty-six people to our house, almost everyone we know in Iowa City. For the reading, we move our dining room table to the side and my students tell Sophie that they’re shocked that we don’t own more furniture to fill the space.

When Sophie’s sleeping, I worry that anything I knock into will wake her, and I fixate on it, even though she sleeps through.

Untitled [Purple, White and Red], 1953

brick bag halo strike

swath writhe absence

sweat cut pits making_

shallow amends more_

orange in yearning_

-Jess Mynes

Mynes’ book, which makes a separate, felt world out of Rothko’s paintings, is entitled Sky Brightly Picked. Because the world of the poems is so contained and yet emotionally twinned to my experience of the paintings, reading the book makes me wonder things I’m already inclined to think about. Questions like:

How many ways are there to know? How many of those ways can be in poems? In what places between the visible and how it’s housed in the body might a poem hang out? Can I write poems in order to figure out the ways of knowing that are available to me?

“it’s one of those / days I want to get / along with everyone / and don’t and / don’t know why” – Frank Sherlock and CA Conrad

Sonia Sanchez has a poem entitled “A Poem for a Black Boy,” where Andrew, to whom the poem is dedicated, is waiting for bus on a corner in Northwest Philadelphia. The poem is composed of two questions about the stares and locked doors that might be part of standing on the street, and a closing sentence in four lines. The sentence reads:

On this cold December morning

waking up from stars

you are the wind choreographing our flesh

you are the sacred water baptizing our tongues.

Every place I’ve been is a little bit the Philadelphia I expect of it, half sweetness and half its impossibility. More questions:

What can poems do for cities, and cities for poems? Can poems be model cities? Can cities be model poems? When Philadelphia, my home city, shows up in my work, what comes with it?

The style’s deep even when we fall asleep / dreaming of the usual: a rap beat - Charizma

Charizma was in his late teens when he recorded Big Shots with Peanut Butter Wolf, who was mostly a kid then too. Charizma was killed at 20, hit by a stray bullet while sitting at a traffic light.

I love his work for its simple seriousness. His flow is its own metronome. He’s absorbed by process, raps about rap, about rapper agility, about amending his own behavior, about how weird America is. “I hope the ice cream truck win wins the race,” he says.

Charizma’s confused about who the bad guy is, and is sure that in moments it’s been him.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/Yyun8ljM0Nk

“My poem sequence is to reinstate (restate) experiencing in space, the mind/eye making estimations/approximations as concepts that are the same as their being in space” – Leslie Scalapino

If I live across the street from a school and the school is demolished, do I understand myself differently? How might people negotiate, to borrow from sociologist Sharon Zukin, “need and taste” when designing urban space, regulating how it is used, or participating in it? Whose taste? Whose need? How do I negotiate need and taste when I put urban spaces in my poems?

“So it became really crucial for politicians and for food bloggers and for you know ordinary people who just liked tacos to put pressure on the city government to allow those food vendors to stay in place.” – Sharon Zukin, on the subject of the popularization of the Saturday food vendors at the Red Hook Ballfields, and the consequences of their enhanced visibility.

Simple Machines

I ran my first half marathon in 2011, in Toronto, a race that’s mostly on the highway. The race was completed, also, by a man who claimed to be 100 but didn’t have his birth records. He ran the full marathon. He was running for eight hours.

Often I think, in writing poems, that I want to reduce or concentrate what exists, to encapsulate whatever in a way that synchronizes its big and smallness. When I’m running, I’m a mechanism for running. For a while, I pictured waking up and being a ball of frosting, where running melted it onto the cake of the day. Sophie told me once that running is pure work.

Model Cities

If one of the uses of poetry is to imagine and build cities, then maybe poets are architects. If a poem is part of a city (a physical part, an experiential part, a mode of city-knowing), a poem accounts for city-problems. Geographer David Harvey considers as utopian the process of imagining new urban spaces, where radicalism begins with imagination:

“Can we think of a utopianism of process rather than of spatial form? Idealized schemas of process abound, but we do not usually refer to them as ‘utopian.’”

A utopianism of process is why I love Charizma, why I dream of cities built by people who love both cities and city-making, for whom it’s both vocation and pleasure. When we work, Sophie and I write poems alone. When we hang out, we write collaborative poems, trading lines.

The Cook’s Companion

In Australia, in 2012, I conducted a series of interviews with people volunteering in a pilot farm to table program, process-minded folks of their own sort. They almost all owned Stephanie Alexander’s big, authoritative-looking “The Cook’s Companion,” an eleven hundred-page cookbook organized by ingredient. In addition to being an enthusiast about how food is sourced, made, and eaten, Alexander is excited about language; hers is florid and lovely. From the book, on eggs:

“The chemistry of the extraordinary egg is fascinating and complex, and even a rudimentary understanding of how and why certain things happen when eggs are whipped, heated, stirred and cooked is of great help to all cooks. Many of the cooking properties of eggs hinge on their ability to trap air (soufflés, meringues) or liquid (custards) and then be ‘set’ by heat. Egg proteins are naturally coiled and linked.”

“Icarus, a long time ago, broke his limbs.” – Le Corbusier

(From Le Corbusier, La Ville Radieuse, 1933)

In 1935, Le Corbusier published a book entitled Aircraft, composed mostly of photographs of and from planes, with some text. The idea of seeing and mapping patterns of building cities from the air was something he’d been thinking about for a while. With its new ways of seeing, an aerial view offered Corbu thoughts about what there was to know, where some of what to know was a feeling:

“The airplane, in the sky, carries our hearts above mediocre things. The airplane has given us the bird's-eye view. When the eye sees clearly, the mind makes a clear decision”

“There are no "details." Everything is an essential part of a whole. In nature microcosm and macrocosm are one.”

“Being neither technician nor historian of this amazing adventure, I could only apply myself to it

by reason of that ecstasy which I feel when I think about it.”

The book itself is attractive, and consumed by process, his huge hopefulness set in his scary didacticism. It’s the work of a man alternately curious about ways of knowing and prophetic as to the modes of the future, so much that he truncates some of his own curiosity.

Catalogue Impulse

https://www.youtube.com/embed/HMU-wXsgyR8

As a child, I wondered about what happened in the factory; how a made thing came out made. Plus, I was thrilled with the crayon factory because crayons were vehicles for gorgeousness, and gorgeous on their own.

I was fascinated by the idea that any made thing had a history of making. In restaurants, I wanted to go into the kitchen. At home, I memorized antiquing guides. I wanted to know the features of a system and how they worked together. I wanted to disassemble the phone, to show all the parts, to name them.

I wonder how a poem might catalogue and obscure at once, how it might choose what to elucidate by hiding other things.

I could move away.

I could get in the car right now

and drive all night,

as soon as I had a sandwich.

Turkey, tomato, mayo,

Swiss, lettuce. It was exciting.

I still had my shoes on. I drove to a truck stop.

It was bright inside and I loved the world.

I bought a sandwich and ate it from my lap while I drove.

When I pulled up to my house it was quiet.

–Arda Collins (from “Spring”)

Davy Knittle

Davy Knittle's recent poems and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Rain Taxi, Denver Quarterly and Caketrain. He lives in Iowa City, where he co-curates the Human Body Series with Sophia Dahlin.