Erik Anderson

Once, Again (Ten Tokens)

- The Yonder

- Once More, With Feeling

- On Monsters

- Many Minimums Don’t Make A Maximalist

- Camera Obscura

- Arrested Decay

- Confirmation Bias

- On the Body

- As for Thinking

- A Brief Note on Strangeness

The Yonder

In Lancaster, in the winter, particularly on the coldest, iciest days – days when if your son’s school hasn’t been cancelled, it’s been delayed for hours – you might find yourself walking with him through the small museum at the corner of College and Buchanan, the latter avenue named for the town’s native son, arguably one of the worst presidents in American history, whose estate, Wheatland, is nearby. The glass display cases that line the museum’s basement are packed full of taxidermied birds, but while your son might be drawn to the flamingo, the snowy owl, or the incongruous wolverine, you’re rather taken by a tiny Ecuadorian hummingbird, whose tail is twice the length of its body. So taken, in fact, that even when it gets warmer you return again and again, sitting in front of the bird at first for minutes, then later for hours. Your questions, you realize, have little to do with wingspan, diet, or habitat. Instead you consider at length the bright green patch on its chest, as though it were a difficult riddle. And then one afternoon, as you’re walking to your office, which is thankfully just down the road, you remember a line from Amy Leach’s essay “The Oracle”: “Such concrete answers,” she writes, “sometimes one misses the old inspired answers.”

Once More, With Feeling

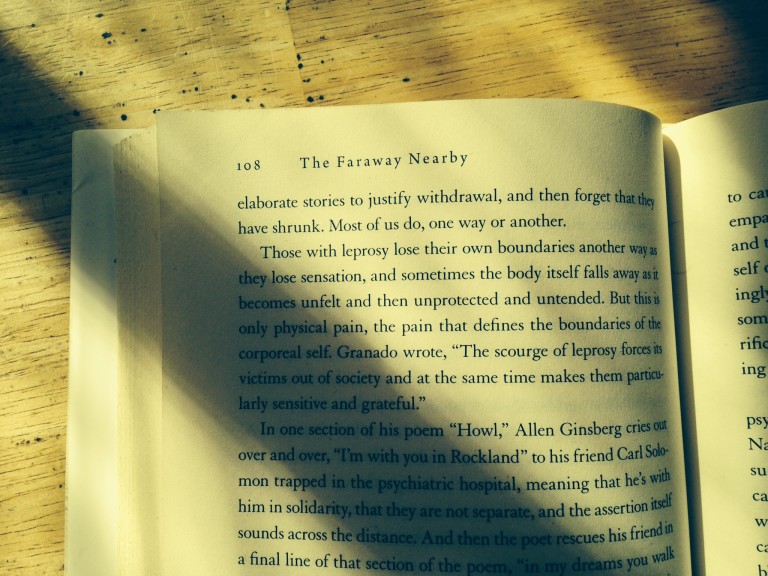

You are a person in pain. No, really. Pain – or more broadly, sensation – defines you. And because “what you cannot feel you cannot take care of,” Rebecca Solnit writes, “what you cannot feel is not you.” We may tell stories in order to live, as Joan Didion famously has it, but our stories end (or rather, contract) at the boundaries of our own suffering. The challenge may be either to relinquish those stories, that self, or to expand them, and it turns out that narrative, situated in the gap between you and me, might be an antidote to the apathy (not-feeling) pain sometimes produces as a side effect. “I think of empathy,” Solnit writes, “as a kind of music.” But how, I wonder, to tune in?

On Monsters

Minor cataclysms happen all the time. Right now, as I wrote that, several small catastrophes took place, and even as I note their passing several more have occurred, are in progress, or will begin momentarily. But on the question of exegesis, I’m divided: do the images in Leviathan illustrate catastrophe, or do they illustrate themselves? Which is the signal and which is the noise? As for that monster of biblical proportions: it’s true we like to watch.

Many Minimums Don’t Make A Maximalist

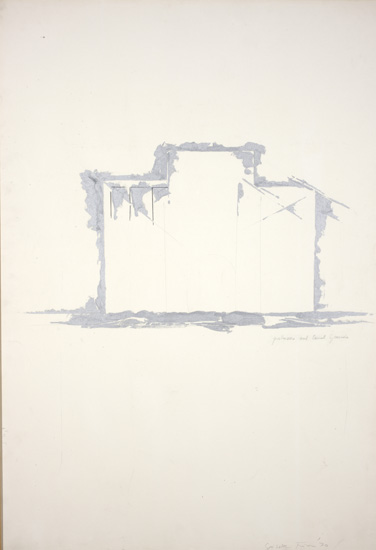

Italy doesn’t mean as much to me as I’d like it to. I have few if any ideas about Rome’s piazzas or Venice’s canals. Like so many places, it exists for me mostly in outline. Dante is one of its edges, Antonioni another. I can make out Calvino in one corner, Matteo Garrone’s Gomorra . Maybe this is why I was so taken, one day last spring, by a series of images done in pencil and silver enamel by the artist Giosetta Fioroni in which Italian architecture (both ordinary and monumental) is reduced to its contours. I suppose I was drawn to her Italy insomuch as I am repelled by the Olive Garden’s: one promises everything and delivers nearly nothing, the other promises nearly nothing and – though it is also up to me to retrieve it – delivers everything.

Camera Obscura

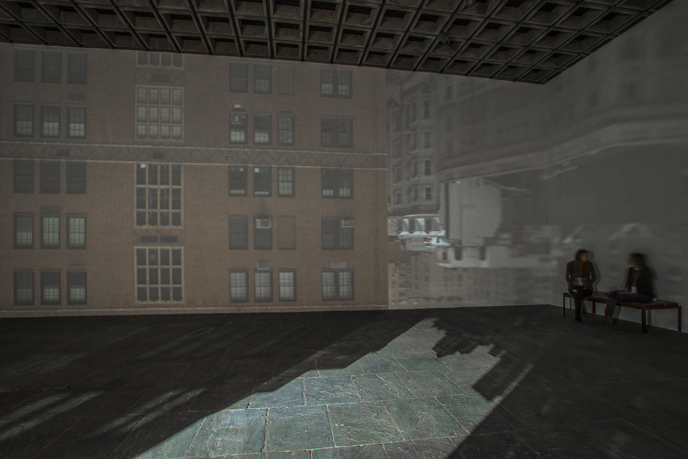

A great artist, Robert Smithson believed, can make art by casting a glance. And in a work Smithson might approve of, Zoe Leonard’s Lens and Darkened Roo (part of the 2014 Whitney Biennial) projects Madison Avenue into the rarefied space of American art, as though you cannot separate the culture within from the culture without. But the work’s magic is only partly due to the simplicity of its aperture: the rest has to do with its scale. Imagine being able to sit down inside a brushstroke, or walking through the curved brass of a trumpet. Now to do this in words.

Arrested Decay

Last year on Walt Whitman’s birthday, my friend Jeremy and I gathered footage of Philadelphia’s crumbling gothic prison, Eastern State Penitentiary, which we later shaped into a film. Our questions were largely about ruin, and they turned towards other structures whose disintegration has been held in suspension, like the iconic dome in Hiroshima which, having somewhat withstood the atomic bomb our forebears dropped on it, has been maintained as a monument to our (in)humanity. (Ruin as metaphor.) Aesthetics, we mused, have their own eschatologies, but in fetishizing destruction “we begin to recognize the monuments of the bourgeoisie as ruins even before they have crumbled,” as Walter Benjamin wrote. (Ruin as cautionary tale.)

Confirmation Bias

Unless it was merely reiterating something I already knew, I may have learned more about writing from watching Gerhard Richter Painting than I did from, say, reading Tolstoy. Life may be short, alas, but process is long. First one layer, then another, and then another. In time one strips these layers away, adds new layers – before sanding or scraping or smearing them as well. Composition is about critical mass, and perhaps one arrives at it less by talent than endurance. To process may be to withstand.

On the Body

There are few contemporary writers I admire more than Amina Tyler, whose creative output, as far as I’m aware, is limited to two striking photographs. Language may be at once a set of abstract symbols and that through which we make meaning of the world, but words are also a fundamentally physical phenomenon, from the firing of synapses in the brain to the reverberations of speech in the air. To use a word is to have a body. No body, no words. Why then does it often feel as though the users of words have forgotten their bodies, have forgotten – sometimes willfully – that to use a word in a disembodied way can lead to degradation?

As for Thinking

Sure, the person in the next cube over attended Princeton or Yale (whereas you attended a state school, the only one to which you applied), but she is really no smarter for it, and neither of you are much brighter, in the grand scheme of things, than your average ant colony. Thinking is not hierarchical. E.g., insect sociobiologist Thomas Seeley identifies “two physically distinct forms of a ‘thinking machine’ – a brain built of neurons and a swarm built of bees,” both of which, he writes, may have “evolved the same basic decision-making scheme precisely because it provides a good approximation of optimal decision-making.” I’m not entirely sure what it would mean to write in the manner that a hive makes honey, but – fuck “genius” – perhaps I already am.

A Brief Note on Strangeness

Deep in the book I’ve been writing for years (Estrange), I ask: “Is this a piece of a previous life, or a life yet to come?” Then, a few pages later, I quote Robert Smithson (again): “The memory of what is not may be better than the amnesia of what is.” Here, is becomes the double of is no , as memory becomes the double of amnesia or, in my own formulation, the future . We see in one the outlines of the other, but rather than reassure us of order the repetition often functions as harbinger. And these experiences, my friend Greg Howard writes, “estrange us momentarily from the world. They break through our ordered, domestic life but they do not make us feel at home. Instead they make us feel the mysteriousness of home, the foreignness of home.” Wherever I am in writing these lines, I am elsewhere, and in that elsewhere I am here. But then who, exactly, is speaking? Why is speaking. Who.

Erik Anderson

Erik Anderson is the author of a book of lyric essays, The Poetics of Trespass (Otis Books/Seismicity Editions, 2010). Recent work has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Seneca Review, Unstuck, West Branch, and others. He currently teaches at Franklin & Marshall College and lives in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.