Judah Rubin

Dependent Form

- Another Water

- The Gestural Hinge

- Ghost Town

- Antiphonic Mimesis

- Eviction Notice

- Language Game

- Hermeticism / Work

- Aphasic Cop(y)ing Mechanisms

- I Want to Know

- Raw Meat Hallucination

Another Water

Footnote in Roni Horn’s Another Water : a woman who came from Paris to London to drown herself in the Thames. Horn notes that no one would do this elsewhere – no one from Canada is coming to the United States to drown herself in the Mississippi, the Ohio, the Hudson River. Migration to death as a means of misunderstanding the static possibility of rest or repose – particularly, in my reading today, Monday, April 28: Orlando’s triggered psychotic reaction in Orlando Furioso –opacity of the environmental solid converted to a footnote of the language of settling; the way in which water is meant to hold its own settled activity, appear as a solid. I don’t think I agree with Horn about these migrations nor about the ways in which we constitute the relative charge of the language surrounding – what about the Rio Grande, or the East River, or the Seine or... but I am interested in the capacity for the sensorial object _river _to function outside an ideal as a place of both initial and ultimate corrupted solidity.

The Gestural Hinge

And so, the functionality of land. Sekula speaks about the use of steam in Turner’s paintings and how wind, particularly as expressed in Turner, becomes an inexpressive component in determining the body of the work so that, to extrapolate, the material body dissipates as a reality. The hinge of this comes, or might come, in the return to the gestural field - as Guerino Mazzola spoke about the other night in his talk “Melting Glass Beads—The Multiverse Game of Strings and Gestures.” The only possible gesture in the face of, say, permanent automation is the gesture of refusal, slowdown, sabotage, complication, of enacting the territory that cannot be mapped, that cannot exist as a set of logistic impositions. Having just received an e-mail from Holly Melgard about her reluctance to publish her sound-based poems due to what she sees as their existence as performance, as gesture – against the score? – I am again caught with the problem of the page and the anxiety of composition. Holly writes to me, “I can't figure out how to get the poem back on the page after reading it aloud.” What is the gestural map of writing and how does the migration of writing correspond to the anticipated nausea of movement’s reification in sense?

Ghost Town

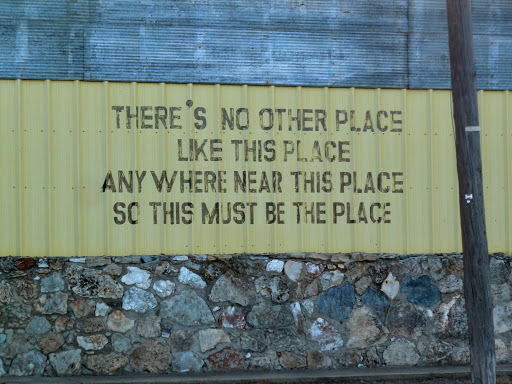

eteam’s ongoing installation, Montello International Airport indicating a possible gestural map, though I feel the complications of it as _site _and I wonder at the condition of loss that travel negotiates. Fugue state – against the emblem of mass travel? Amnesia as disappearance of and into facilitation of legible plot? The materiality of the abandoned object and the construction of habitation appear in this piece in such a way that it has a real effect – one _can _land an airplane, in a way that the Prada store in Marfa was just another colonial beacon, building an opera house in the jungle, exporting democracy, etc. If the American avant garde has become a jewel shop per Heriberto Yepez, it’s only right that the Prada store in Marfa was almost immediately broken into. In Texola, Oklahoma, a town that didn’t refuse to die, two adjacent sides of a building : “No Place Like Texola” / “There’s No Other Place / Like This Place / Anywhere Near This Place / So This Must Be the Place.”

Antiphonic Mimesis

Lewis Freedman, Robert Kocik and I are talking in a recording I made while Robert and I were staying at Lewis’ in Madison where we had read earlier that day. Lewis is speaking about 19th century Hebrew novelists – I assume he is talking about people like Abraham Mapu – who at that time are attempting to write in a newly modernized language that hadn’t been used in everyday life in 2000 years, or, really, ever considering its resuscitation as a modern language involved such a hybridization of vocabulary at once. The puzzling place here, not of translation from the language to its surrounding languages but the attempt, by Mapu and by people like H.N. Bialik to write outside of mimesis or the possibility of mimetic similitude seems to me the problem of the transferable idiom but also of the perspectival thirst for understanding, which is to say that away from the elephant’s tail or trunk, we might be able to glean insight through a notational station(ary.) What did Zamenhof have on his grave? A star made of green gems – tourmaline, aquamarine? – mosaic of possible linguistic forms.

Eviction Notice

Last night, Kaye went to see Goran Đorđević’s Salon de Fleurus, a fictionalized reconstruction of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas’ Parisian salon. Tomorrow, he will be evicted from the space after years of occupying it. Notable that this space carries with it an emblem of ficticity to me both in its spatial dimensions, but also, with regard to its place as inhabiting. The grammatical conceit here is one of imaginary or shadow linguistics as concern a space, and eviction, all past eviction occupies this same location. How does the vantage of a depleted historicity affect me, us? It reduces my capacity to actively fictionalize representation, to bring representation out of its power of shadowing, and, so, disrupting the circulatory potential of defacing the site of history. The space of eviction for one who never inhabited—there seems to be no balm for that. Jerry Seinfeld, last night, in one of his more insufferable jokes, “Parents like to drag kids to historical sights. I remember going to Colonial Williamsburg and you see the supposedly authentic blacksmith there. He’s got the three-cornered hat, knickers and the Def Leppard shirt.”

Language Game

Reading Ariella Azoulay in Critical Inquiry and Divya Victor’s Things To Do With Your Mouth. Azoulay - vantage of collaboration, yes, but also the way that disaster implies the self in its supplanting the other. And in Divya’s book a recasting of the mouth or silence to force the disaster of silence back into the mouth of its implication – parallax as a measure of implication; a test of speaking as poetry and of the means by which conviction – as Rachel Blau Du Plessis relates as a concept in Zukofsky’s A Test of Poetry – builds a commitment to form and content as extensions of political views and poetical constructions. So what is that simultaneity? It seems that Zukofsky on Lewis Carroll makes sense to think through: “the nonsense recorded its own testimony.” Testing of: casting the net of effect/affect in concatenation/con-cantation. The implication and extension of as possession and result move outward into space.

Hermeticism / Work

Over the past few weeks, I’ve found my conversations with other writers drifting away from the social/poetry gossip and further toward the hermetic dissociation of “doing the work.” I’m quite glad for that. Often I/we think of/fear a dark ages of poetry when poets aren’t bound together by the fact of their mutual engagement in a form, but I wonder about the inherent limitations of speech are and the failure of a socialized poetics that constricts the possibility of mobile thoughts, which seems to imply a forced cosmopolitanism that accounts only for the permanent work of “translation” as commercial entity. The question becomes, in a binding system, what do you have to offer, which is usually the myopic capital of one’s immediate concerns without the corporeal application thereof. But then, who’s “Dark Ages” were they, anyway? The question of the binding socius, the dogmatic socius, renders the life of poetry one where the jouissance endemic to consumption becomes a permanent entity.

Aphasic Cop(y)ing Mechanisms

Language, to me, sick with a head cold, is a means of coding the rotating speaker of experience as against the body of stable representation. The phasing of meaning as Doppler affect – or ambulatory policing of dealing with it– one’s hand. In the back of the ambulance the paramedic kept my morale up by telling me his favorite stories: brains spilled on the sidewalk, the logs came rolling off the back of the truck, right through the windshield. Who was speaking? Why did they keep calling me Rubin, Davis, a recoding of my father’s name (David), the street I grew up on, (Davis), and a reversal of the position by which I might, generally, assemble my genealogy? The semantic repositioning of gestural thought: heavy with fever, I wandered out into the night, the sidewalks were split into geometric paper cuts – sometimes, still, returning to sap a representative body for extension.

I Want to Know

I hadn’t heard of Charles Olson until I listened to the Fugs’ I Want to Know the same day I took four hits of acid and took a tour of the United Nations alone except for the German tourists I somehow got lumped with in a tour group. Olson remained – I suppose still remains – a major touchstone in my understanding of literature primarily because I hadn’t ever seen the crosscutting of history done in such a way as to understand the archival object, itself, as poesis, as a means of understanding the breaking open of the body of history “solely to know.” When I first read Susan Howe, I had the same feeling – a sort of inexpressible love and thanks for these poets having broken open the spaces of an historical concordance, that the work of poetry was to find correspondence between objects and to consider a Whiteheadian space of relation and process. I sat in my room and listened to the Fugs, whose name I had encountered in Ted Berrigan’s work, for hours until my roommate came home, and admonished me for lying in our dorm room stark naked, crying, while Ed Sanders punched his voice through Maximus.

Raw Meat Hallucination

I haven’t eaten meat in many years – my last lapse was at a barbecue where they handed out temporary tattoos of gall bladders, and how could I resist a shitty hamburger in that situation? I do, however, often dream in raw meat. It is, to an extent, this drawing that my friend Becka Hartz sent me years ago, that stays with me – a dead rat bleeding out into the street accompanied by the familiar “Wish You Were Here.” The impersonality of the body as a potential site for experience, what I am trying to reject in my own work, seems to stem from an hallucination I had hiking the Appalachian Trail five years ago, or so. There was a tremendous amount of gnats bombarding us, and the stream we were hiking along – cool and replenished recently by the frequent late spring rains – changed before my eyes away from a reflective and narcissistic surface to a river of ground meat, pink and awful, crawling with maggots. The objective ideal, to return to Roni Horn, is always corrupted by the fact of obscurity, which is to say the objective ideal of the conceptual conceit as well. The politics of all water is the rotten spume of a wellspring that nourishes and satiates in and of its decomposition.

Judah Rubin

Judah Rubin is the author of, among other chapbooks, Flag of Convenience (Well Greased Press, 2014), Phrenologue (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2013), Phrenologue (O'Clock Press, 2013). He is a curator at the Poetry Project, the SEGUE foundation and elsewhere, and the publisher of Well Greased Press. He lives in Sunnyside, New York.