Michael Gossett

Bead

- Trespass

- Deer

- Moses

- Bar

- Genesis

- Bead

- Quasi-Intelligibility

- Riddle

- Ellipse

- Techne & Physis

Trespass

To trespass is to enter something set apart. To set a NO TRESPASSING sign is not to say NONE SHALL ENTER, but MOST SHALL NOT/WILL NOT ENTER. One can easily invent an ahistorical pseudo-Latinate language in which the original term in translation curiously means both itself and its contrapositive (the uncanny is both “homely” and “unhomely”), and with this invention the sign reads as its own question, i.e., WHICH OF YOU WILL ENTER? Speak shibboleth and I won't shoot you at the veil. If you are allowed entrance to the holy place, why don't you just say so?

Deer

When I moved to Maryland from Tennessee, I took an underground studio apartment facing a stream that dumps into a lake a mile or so away. Between the front steps and the stream is a mostly empty park where the deer who live behind the lake come out at night and occasionally stand among the park's swing sets and totem poles: 'occasionally' if only because the sight of them came to be an occasion for me more than simply an experience. How else to explain the uncanniness of the deer―those I had grown up spotting in commercial farmland from a car window on Highway 64, standing three or four at a time, always far away from me―their being so close to my car, in my garden, at my bus stop, above me looking in through the bedroom window? And among the totem poles, themselves a kind of axis mundi, how else to experience them but as so other as to deserve my reverence and obsessive attention?

Moses

These things with antlers, horns―the way a mistranslation in the Latin Vulgate once gave Moses horns when he returned from seeing the back of God, horns that endured in sculpture and paintings for centuries―perhaps they too have seen the back of God, returning, presenting themselves, or giving their image to me on behalf of another. An atheist, I know no other―but then, perhaps the very reason why they would be given to me of all. Paul. As a person of gratitude, I have been looking for ways to show thanks for a gift that I do not understand. There is a long history of poem as praise song, but with what language and in what form does one praise the world when his confidence in there being no giver is equal to his confidence in the intentionality and deliberateness of the gift, i.e., what in the soon vacant room opens the door when I speak shibboleth through the key hole?

Bar

The poet Michael Palmer visited the University of Maryland in my last year and sat in on a workshop. He was talking about a poem he wrote that featured a bar. He said that Philip Levine, US Poet Laureate at the time, and a very narrative poet, once did an interview with someone on the radio and the host was like, "Phil, this poem about a bar: I know exactly where that bar is. I've been there. Your description is so spot on that I know exactly that place and you captured the essence of it perfectly." And Palmer said that his own poem about a bar is fundamentally different because his bar is a bar that you could never actually go to, not even if you wanted to. No one could say or will ever say about his poem, "I know that place. I've been there," because it exists in the mind only as an imaginative experience or metaphor.

Genesis

I asked him whether he didn't think that had something to do with the purpose of poetry, which has a long history of being linked to naming. In the Old Testament, to name something is to have control over it (Adam names animals: man controls nature; God names the ten commandments: the supernatural controls human morality; the burning bush / "I AM WHO I AM": God won't reveal his name and cannot be controlled) and often the idea of naming a thing is to bring it into existence (God speaks and the world is created). Blah blah. So IF poetry is an act of naming, what is the more important or necessary act: to re-name the thing that already exists in the world, or to name the thing that wouldn't exist unless you named it? Put another way, is the greater/more creative act to "re-create" the experience of going to a bar that you have been to before, or could go to to verify the poem, if you wanted; or is it greater to "create" an experience that isn't a replica of a real event but is an experience/occasion only accessible VIA the poem, i.e., one can experience your bar without your poem, whereas there is no experience of my bar without mine.

Bead

The concept behind BEAD is like the rosary bead/prayer bead, where there is a certain language that corresponds to a certain object. A Hail Mary corresponds to the bead on the string, and you pray the Hail Mary in a very specific way. You can't improvise. It is litany. Someone created a specific phrasing for that prayer and it forges an eternal link between object and utterance. BEAD = HAIL MARY. And the string literally holds the objects (beads) together, but it also holds the language(s) together in a more metaphysical sense. So what would it mean to create a language for a different object (not a bead, but a deer) and what is the "string" that holds the me-bead next to the deer-bead? It's almost a question of "Why am I drawn to the things I am drawn to? Why am I being brought to them?" And to answer the questions will require you to repeat a lot of terms and the language you use to describe it all sort of compounds upon itself and it sounds like you are talking in circles—well guess what? That sort of thing is what makes for good poetry! repetition! repeated sounds! parallel syntax! patterns, then breaking of patterns.

Quasi-Intelligibility

“[P]rolixity [too many words] is the surest way to achieve quasi-intelligibility but its riddling effect can be produced by other means...metaphor, syntactical/lexical high-spiritedness, pronounced sound patterning, parataxis—anything that serves to complicate the uptake, slow the flow, & draw attention to the language itself before that which it indicates.” —Timothy Donnelly

Riddle

The riddle is an intriguing exercise in metaphor in which the tenor (referring to the concept, object, or person meant) is obscured from the interlocutor with only a flimsy vehicle (the image that carries the weight of the comparison) standing in as a point of partial resemblance. If a horn is like a holy person, it is only because both share in a third, triangulated point as objects inscribed by elevation (the horn extends vertically upward, mimicking the transcendence of man to the divine). We could say that horn = holy by means of elevation, i.e., A = C by means of B. Water = bone by means of iceberg. A three-legged creature = an old man by means of cane. The uptake of C by A is complicated, slowed, by its insistence on an analog, B. So if one seems to have a hard time talking directly about the thing on his mind, perhaps it is because such a thing is hidden or severed from him and the world is but a seemingly infinite series of vehicles of which life is a trial-and-error process of illumination and solution.

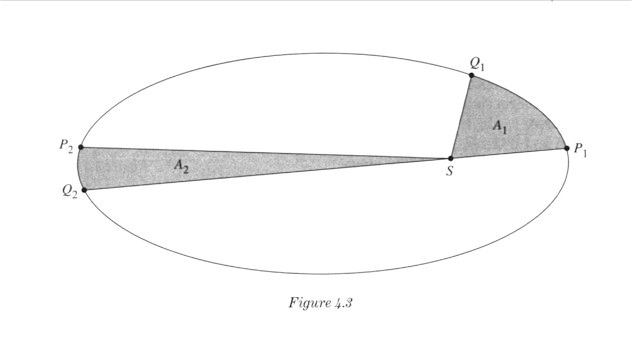

Ellipse

The planets orbit the sun not in a circle, but in an ellipse. And the speed at which they move, Kepler learned, changes based on their proximity to one of the elliptical foci. When a body is close to a focus, the body moves quickly, gliding over great distances on the perimeter a few long skates at a time. But when the body is far away from the focus, it moves slowly and traverses the perimeter inch by lowly inch. The Second Law tells us that despite the energy and speed of the former and the lethargy and pace of the latter, each sweeps out equal portions of area in equal time, which suggests that getting close to the subject is as important as being close to it, and that most of our time will be spent on the edge but this does not make it wasted time. The empty space between us and our focus is there at all times.

Techne & Physis

A unique and defining experience of the 21st century is, in essence, making the important distinction between the real and the apparent, the original and the derivative, the physis (that which has a beginning in itself) and the techne (that which has a beginning in another). Though these objects of techne can often be 'made' to seem and feel very much like objects of physis (consider, for instance, some of the great technological achievements of our era: cloned cells, artificial intelligence, genetically altered food), despite this, the human being possesses a deep and abiding, perhaps even hardwired, commitment to maintaining the distinction between the truth and its, even very close, approximation, and perhaps, too, as a result, a remarkable evolutionary ability to sense instances of the blurring of these terms even when the actual distinction may be difficult (or impossible) for them to make. Navigating the fine line between these categories, it seems, is a uniquely human experience made even more unique given our technological epoch. —physis, Leigh Johnson

Michael Gossett

Michael Gossett is an arts grants archivist for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and a books editor for Thought Catalog. His series of conceptual poetry reviews have appeared in The Volta 365 and his conceptual poems have appeared in broadside form through Black Aggie Press and in the The Found Poetry Review, Happy Dog Mom Lit Journal, and Let People Poems. He lives in Astoria, Queens.