Sarah Francoise

Your Life Is Like A Kaleidoscope

- Model villages/Henry and June

- Douarnenez/Georges Perros

- Your Life is Like a Kaleidoscope/Bars

- Cow Bells/Dreams

- Baking powder/church candles

- Shingling/the Hibbing diaries

- Shipping forecast/lists

- Shrine/Orgonon

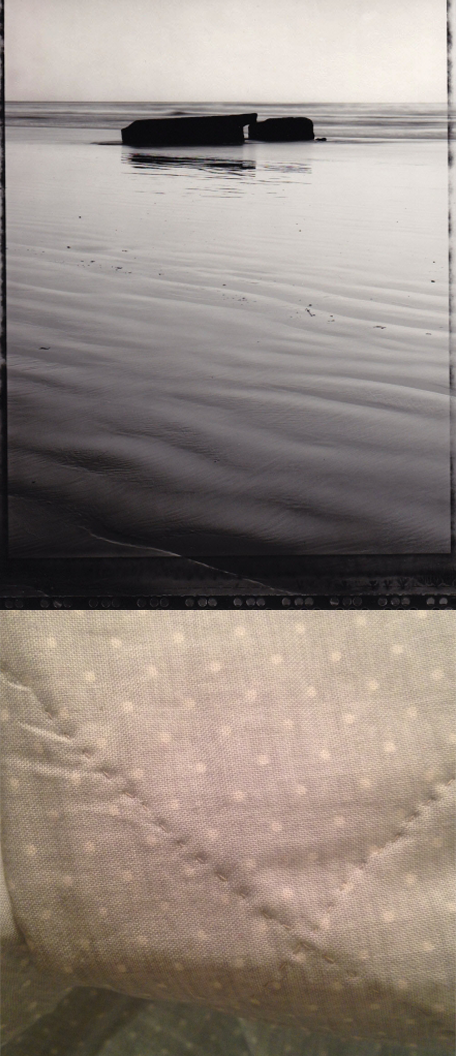

I have lingered inside a WWII stone crusher, and under our mothers’ quilts. The plant at Tréguennec siphoned pebbles off the beach, grinding them into concrete dust for the Germans to pour their bunkers. Our mothers quilted for decades, leathering their fingers for the likes of us. The sand on those dunes was criminally soft, and the mouths of the stone-wagon tunnels were left gaping by the sea. The quilts crushed us into our berths, while inside the anti-aircraft blockhouses, the thrum of the wind kept us still. The waves were gathers in the quilt; the cotton dashes, a sea foam rickrack. The blockhouses had barnacled windows the size of mail slots. Both were orthogonal. The quilts were stiff and heavy, even after a tumble dry, but the bunkers were weightless in the sand, and danced at the whim of dangerous tides. Our mothers signed their quilts over to us. The bunkers were endorsed by those who found them, sinking obloquies on a long white beach where the Atlantic spits out her dead medusas.

I was a virgin, back in 1988, and for a long time after that. Karate Kid was my Jesus: white pajamas with a lime green dragon and a black belt. Later, friars with names like Paul and Pierre rapped my Hail Marys with their bony twitches. The Catholic churches were dustless and harsh, and I tested their echo by stomping down the nave. God ran my school, and God was on the sleeve of a Frankie Goes To Hollywood single. God was everywhere and I got banished from Sunday school (and tennis camp). In Brittany, my mother collected clay virgins that were soft and devoted, and spoke of a messy nativity. Even the robes on those statues —Sainte Marie, Sainte Anne— were vague. Blue bled into white. Veil bled into flesh. Holiness bled into labor. And in the skirts, a baby is born. The same is true of the Mexican virgins, with their impossible titles and gilded curves. And the mothers hover: the statues, over a biscuit eminence, the painted Mexicans, on the shoulders of angels. High, high above Paul and Pierre, with their white knuckles and instructions.

Model villages/Henry and June

The model village at Bourton-on-the-Water is a one-ninth scale replica of the real village, and June craves a little vulgarity. The bells in the tiny church chime like real bells, but fall on deaf ears. June comes and goes, relieved she’s only time passing. You’re up to your knees in architrave. Ears get chewed — ding-dong ding-dong. The floor of an inch-deep pond has the copper sheen of a wishing well, while elsewhere, there is lucky sucking. You could be a giant on the bridge. You could play marbles with the cabbages. You could seek Henry, erroneously, in John. You could post fingernail-sized letters in the red ankle-high mailbox. You could take all your clothes off and kneel. You could spy on them, through the window, and ascertain the altar. You could read frigid sonnets in a blizzard, in a house full of your shrunken children. You could keep an unexpurgated diary, yourself. You could have constant slips of the tongue. One-ninth is the ideal scale. A model village has no need for model citizens.

Douarnenez/Georges Perros

In Douarnenez I sailed a diminutive tuna boat around an island guarded by a grieving cow. Whenever I capsized, I thought of her calf, tumbling off the cliff, legs splayed, now pickled in the ocean brine. It didn’t help that my father told me seaweed was the hair of shipwrecking mermaids. Or that he once caught a bird at the end of a fish hook, which tore out its larynx. Or that a madman with no face dragged me into the ocean by the hand, until the water reached my chin. Or that I got lost on board a four-mast Russian training vessel (with nuclear capacity), and ended up in a mess of sailors. Or that there were reports, every summer, of missing children who’d sought solid footing in the heather, too close to the cliff edge. It didn’t help I got yelled at over mussels, that night a big wave crashed on the jetty, seasoning everything in sight. By the age of 14, I was terrified of deep water. The tuna boat had a red sail and a black hull. “I have never heard a fisherman say that he loves the sea,” wrote Georges Perros, in the same port.

Your Life is Like a Kaleidoscope/Bars

I came to New York with nothing. Yes, I know, everyone did. I stole crockery from Chinese restaurants, and they repaid me in fortune cookies. Your Life Is Like A Kaleidoscope. At first I misunderstood, and thought: yes, certainly, multi-faceted. How banal of the zodiac. Then I worked harder and realized that, by kaleidoscope, they meant the optics. The wings and the eyepiece, the prism tunnel, the twist of a wrist. Not the mosaic, not the arrangement. Dichroic marbles in object chambers — in layman’s terms: love-things on shelves. When I came to New York, I worked in a bar. Yes, I know, everyone did. Perhaps that was the arrangement. Perhaps the mosaic was the bar, where the motes of life are laid out like cheap jewels waiting for a thread. Where your neighbor’s fake rubies purple your glass sapphire. Where orphans — yes, I know, everyone is — trade in secrets and weights, and clink chances.

Cow Bells/Dreams

I read in a reputable dream dictionary that a cow bell means both the start and the end of love, trepidation and fearlessness, abstention and adventure. If it is ringing, it means you will dream of a cow bell. If it is a cow bell, the metal will be hammered. If the metal is an alloy, the cow was mendacious. If the ring is a din, then you are done. If dreams are a series of decisions made out of wedlock, then you never slept at all. If the bell is attached to a cow, fill out a Jungian personality test. If you win, you’ll dream of a cow bell. If you dream of a cow bell, it means you will find an identical cow bell the next day, in a junk store in Brooklyn. The leather handle will be fringed with those red and gold tassles you saw in the dream. The cows will come down before winter, and leave the Alps to go blue. And if the herder has one of those Cocteau foreheads, then you are doomed, in dreams, to chasing men with creels.

Baking powder/church candles

Cookery. It sounds like a special branch of witchcraft, practiced in kitchens. In December I’ll mix my daughter’s birthday cake in my grandmother’s mixing bowl. The family confessor, San Rocco, patron saint of dogs, will stir in the sodium bicarbonate. Baking powder to rise the cake and resurrect the dead. Grandmothers and grannies and great-aunts, climbing out of Victoria sponge, tossing sweet battered commas — painted with egg whites and sugar — in a hot pan. And church candles to keep the sugarplum ghosts blithe. I can’t remember which ghost I first made the promise to, only that I kept it. I lit candles for all of you in Paris, Colston Bassett, Barcelona, Pont-Croix, Derby, Marrakech, Pointe du Van, Saint Jorioz, Saint John the Divine, Nottingham, the Sacred Heart and Forte dei Marmi. In the new year I put them on paper boats, to float down poisoned creeks and Europe’s purest lake. I remember: it was you I made this contract with. You, the baker, who walked up the motorway like other old people.

Shingling/the Hibbing diaries

In Hibbing I bought eight years of diaries belonging to Arvid Kangas of Kinney, Minnesota. They are like an arrow slowed down. Made a deposit at the State Bank. Bought an overcoat. Went to Minneapolis. Fixed the stone wall. Shingling is like building a stone wall. You don’t grab the first stone or shingle on the pile. You consider size, the perspective of two shingles ahead, and anything else you want, like knots in the wood, shade and texture, lines, and all the other markings that make each shingle its own stone. I learned how to shingle in Maine, in 2008. The first few rows yielded very little but technique. But seven rows in, the pattern of a job well done began to emerge. Between the novice and the knowledge. Between 1911 and 1919. Between Maine and Minneapolis. Between blank slates and record. Between Arvid and I. Between an old brain and a new barn.

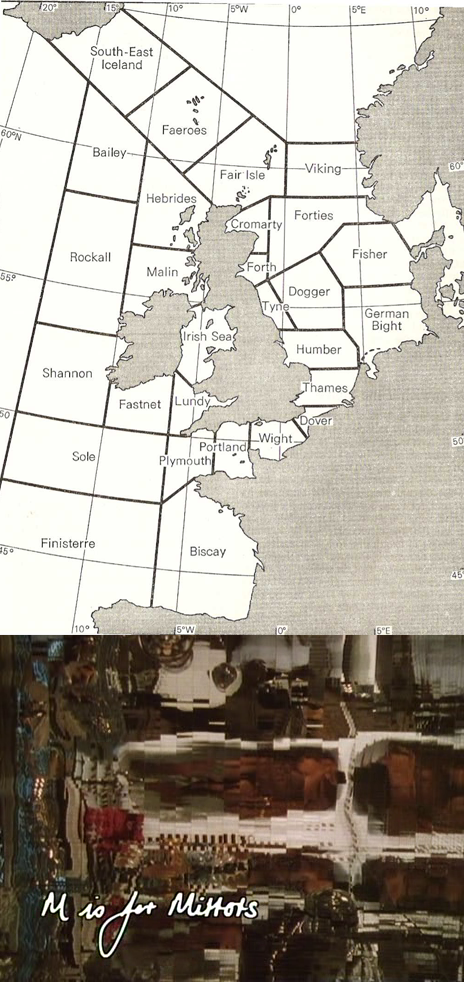

Shipping forecast/lists

At some point I started listening to other people’s gale warnings. I’m not sure why. Perhaps it’s because I knew Finisterre long before she became the flamboyant Fitzroy. Perhaps it was a wish to be both moderate and good, like visibility on the Celtic sea. More likely it was the strict format of the BBC shipping forecast: charts, clockwise reports, and chunks of sea named after things as immovable as sandbanks. Grids don’t disappoint, and everything is better in a list. Take bathrooms. I mean, take films. My favorite list is Peter Greenaway’s 26 Bathrooms — an A to Z of poetical hygiene. It’s also my first experience with eroticism. There’s the woman in a red leotard eating a wet cucumber. And then around I is for Italians, there’s that sentence that has the words bath, bread and jam and scandal, in it. Putting your senses, your bathroom, and your sea in order. Bodies of water, toothbrush, North Utsire, bidet, squally showers, a low, wet hair: the weather’s going to be beautiful.

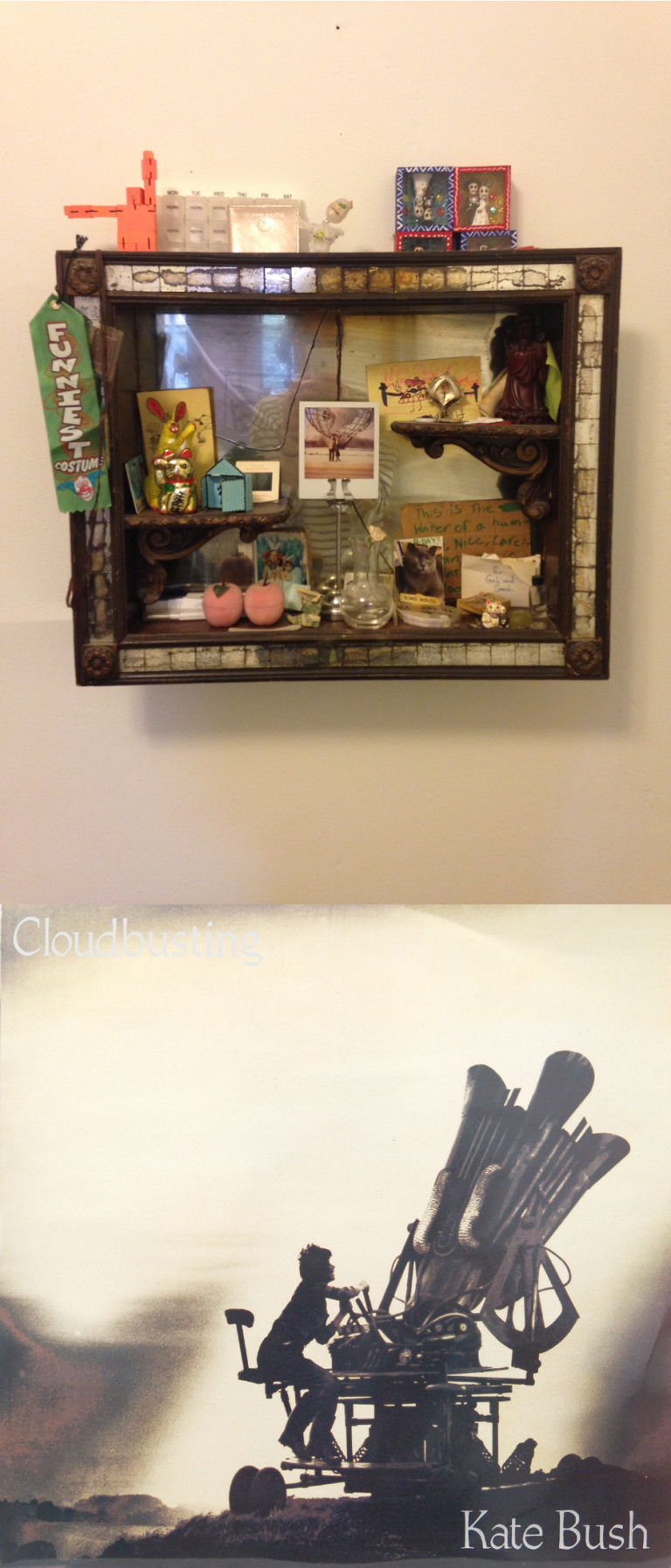

Shrine/Orgonon

We’ve carried our altar from house to house, its elements bubble-wrapped, unlike history. To gather memories like snow gathers around dust particles. The one-eared Oaxacan bunny, a vial for the relic of a humble water balloon, a post-it note with a question mark. A scrabble letter and two love letters, dense with promise. A pill box. Toothpicks in aspic. The receipt for a wedding feast and the prescription from a miscarriage. A medal for the funniest costume, that time you went as a picnic table. Our vitrine is like a Sicilian volcano, with the fossilized eruptions of our life, its periods of inactivity, and a gift shop for crazies. Like the gift shop at Orgonon — remember? — where we got the pamphlet we enshrined, that time we renewed our vows under a cloud-buster, without even telling the other.

Sarah Francoise

Sarah Francoise is a writer/translator living in Brooklyn and in Maine. She recently wrote the film Vacationland, which won the Grand Jury Prize at the Boonies International Film Festival, the film Ursula, and a children's play called The Line. Her writing has recently appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Volume 1, Poems in Which, Tin House, and Hobart.