Veronica Martin

People Sit Where There Are Places To Sit

- Mapping the Heartbeat

- Flags

- Obsessions

- The End of the Day

- People Sit Where There Are Places To Sit

- Some Fruit as Remembered by the Dead

- Good Luck Charms

- Wind

- The Agneses

- Color Is No Tourist: Saturational Concept

Mapping the Heartbeat

Image credit: Marshall Walker Lee

Travel of late has been searching for heartbeat. Artist Dario Robleto says “The Boundary of Life is Quietly Crossed” when we go traveling within a human for her heartbeat and when we go traveling into outer space bringing our own. Between the fabric we use to cover our skin and our skin itself is a “thin wall of air,” said Bill Cunningham about the couturier Charles James, who knew a thing or two about how a swath of fabric should lay on a shoulder, a waist, a wrist. The same is true for the fabric of time, as well as for the fabric of another person, as well as for the fabric of a place. Our apartness, a basic source of despair in the camp of we-are-alone-forever philosophy. Chris Marker, photographer, cineaste and avid traveler who created my favorite travel guides—Petite Planete—for the Parisian publishing house Editions de Seuil in 1954 says, referencing Proust, “to everyone their Madeleine.” To everyone their involuntary memory and the raw material that precedes it. The rawest of that raw material could be the heartbeat. The a priori caution at the onset of a forest of objects and forms. “Baby, baby, can you hear my heartbeat?” calls the sixties popbubble collective voice of Herman’s Hermits. It’s the drum roll leading us into a place full of hot teas and cool blondes and Metro stations and palms. A through-the-glass flânerie into one’s own memory. And we are often immobile for a time in the face of it. “Lose yourself to improve yourself,” an old favorite from the book of Wu Tang wisdom. To lose yourself in the heartbeat of another place and another person is to find yourself in the thin wall of air between the body and the fabric that defines it. I think Joan Didion does this in her site-specific Californian, Los Angelian inquiry into freeway systems and water supplies and cults. Holding herself between the infrastructure of a place and the infrastructure of herself. Traveling is a way of expanding one’s own infrastructure and as a result moving the walls of a place. Toes in the pool of Palm Springs, fingers in your hair, body in the neutral heat between. “There is only one heart in my body, have mercy on me” says Franz Wright echoing a common plea. For the times when we become momentarily invisible to ourselves, overwhelmed by a new environment or person, lost in the unmapped in-between, a guidebook would be nice. Instead we have words, gestures. The ability to make handsome sense with a new mantra: keep critical to take care. That and: show up. Chasing heartbeats, tuning in and out of one’s own, bouncing around to two separate drum beats. Making lyric sense of them. Also called: mapping.

Flags

Image credit: Agnes Martin

In August I visited a friend in Texas. I’d never been to Texas before and it seemed very full of space and a heat I was ready to be afraid of but in the end walked away from dolefully. A lot of stories and particularities and personalities about Texas kept at me after I left, but none so much as the “Come and take it” flag. One of the early stories I heard from my friend as he played tour guide was the one about the Texas Revolution and the Battle of Gonzales. Mexico had orders to seize the object of Texas’ pride—their bronze cannon—and when a small group of Texans kept them from doing so, Texas further added to the blow of Mexico’s defeat by sending them a bold flag as message, reading “Come and Take It” below a line drawing of the cannon. Right or wrong, the power of a flag is unquestionable; so much respect lies in those fabric-body-borne messages of belonging, kin and community. Flags are one method of showing, among many others. Yet the flag as object is deeply beautiful, naturally defiant in its place at the top of the flag pole and yet also naturally elegant no matter if it’s at rest or tempted by the wind. Agnes Martin says, “We need more and different flags.”

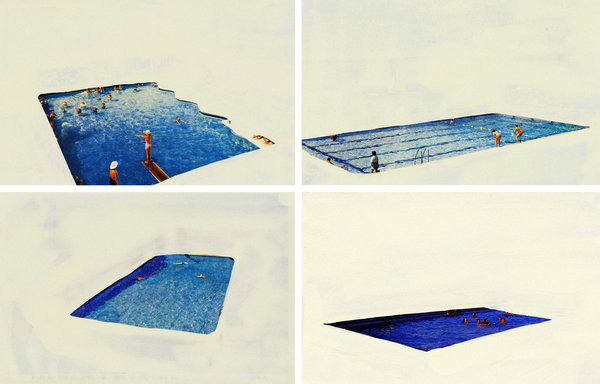

Obsessions

Image credit: Leanne Shapton

Source material, as this column seeks to lay out as specimen, is born often of obsession. To write about any one thing out of personal volition we must be somewhat possessed by it, and it can be a slippery slope from possession to obsession. Especially if the object or idea possesses us first, the obsessor. To obsess is different and perhaps more dangerous than holding mere interest, but it’s also a lot more interesting. I love hearing about friend’s obsessions (thin capitals, a beige pump with a white dress, the number 9) and I love reading into a magazine’s quarterly obsession (the black napkin, arriving alone, the clip-on). Each obsession is full of personality, character, a kind of swaggering candor the very “classic” and the very “of-the-moment” share. Obsessions are a method of dressing, just like the flag is a method of showing. I say, a flag for each obsession.

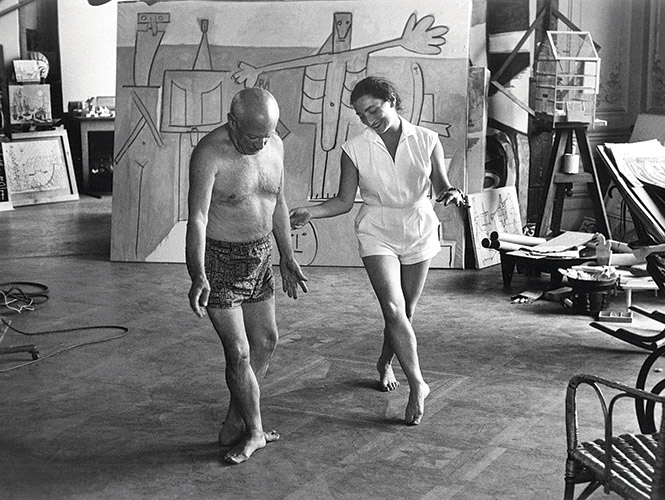

The End of the Day

Image credit: David Douglas Duncan

The person at the top of my favorite end-of-day ritual list is Picasso, for whom that golden hour meant simply sitting back and looking at what he’d done. There is a photograph in some issue of Vogue or Vanity Fair of Picasso standing among his numerous canvasses, propped and hung and leaning around him. It’s an image that’s stuck with me, as I think end-of-day rituals or transformations or whatever you want to call them are worth admiring. For Joan Didion the end of the day means an inarguable hour alone with a drink at cocktail hour to slide away from the day’s work in a way allowing her to take things out of her writing and put things in from a different perspective. Hemingway ended his writing day when he knew what was going to happen next in whatever narrative currently laid on his standing desk, thus conserving a little kinetic energy to take into afternoon activities. How we put away one project and move through the gauze between work, work and everything outside of work is like trailing a piece of fabric through a wet garden… we pick up dew, soil, and a few green smears in the fresh air between modes of concentration. Moving away from something and toward another demands some level of decay and some level of restoration. Attachment and flight. “The alchemical view of the soul’s progress makes room for the putrification of decay, and melanosis, or blackening—shadow aspects highly valued in traditional alchemy,” says Thomas Moore. He’s not talking here about the soul in art, per se, but I think our relationship with our work mirrors our relationships with other living beings.

People Sit Where There Are Places To Sit

Image credit: The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1988)

When I was an undergraduate Journalism student I had a professor who dealt with a broken heart by running into the unknown. A love leaving meant she left, too, to Mexico, China, India, Guatemala, usually finding some kind of immersive volunteer project. She studied relationships and taught courses on solitude and communication. In one of her seminars she spent an hour graphing out and drilling into us how important it is to know your own and your partner’s desired amount of togetherness and apartness. She also showed us a documentary on urban spaces and city planning: The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces by William H. Whyte. As a sociologist, Whyte studied, among other places and things, Manhattan's public plazas. One of his very basic yet in my mind profound takeaways from this particular study had such an impact on me it’s one of those rare moments I still remember in full scene: late spring afternoon, filtered sunlight, lights off in a warm classroom on the first floor of a building surrounded by a low hedge and filigreed trees, and this sentence in white against a black background: “People tend to sit where there are places to sit.” At the time, alone and over-thought, I internalized the concept. People sit where there are place to sit in public plazas and, my interpretation, people sit where there are places to sit in other people. In other words, if you make a hospitable environment to attract those you wish to attract, you first have to organize that environment in and for yourself. Also, if all your chairs are already filled, all your seats taken, there will be no room for a new person, and if alone, no opportunity to fall in love. I just read Dottie Lasky’s “Never Did Amount to Anything” wherein she says “If somebody asks me what I like/ It’s not food or sex/ It’s looking at things and being in love.” In “Why Poetry Can Be Hard For Most People,” she says “And all you can hope for are the people who put that calm in you.” It’s something a little like this, I think, simplistic and calm, putting chairs in places chairs aren’t usually and seeing what happens. It’s both a waiting and an acting upon—an economics of self on lunch break. If I had to choose a set of words to live by, Whyte’s would be those words. In this context, running into the unknown becomes an exercise in creating space for an internal unknown, more places to sit, added chairs, an expanded plaza, making space for the unknown to find a place across the table from the known, each with their brown bag lunch.

Some Fruit as Remembered by the Dead

John Berger, in his book Here Is Where We Meet, offers a few sketches of various fruits as remembered by the dead—melon, peach, greengages, cherries and quetsch. “Our peaches blackened in the sun. A crimson-black to be sure, but with more black in it than red: black like iron which has been heated red-hot and has been slaked and is cooling and gives no warning of the heat it still holds. The peach of the horseshoes.” About cherry pits he says “It felt more like a precipitate of your own body, a precipitate mysteriously produced by the act eating cherries. After each cherry, you spat out a cherry tooth.” About the blackish-purple color of the quetsch, the fruit of song, “These two colors made us think of drowning and flying at the same time.” This book breaks the clock over its knee, so to speak, and offers its two halves palmside up for us to crawl between. Which is to say, there are moments with Berger where one feels spatially suspended, hovering in the moment between letting something go and holding onto it. The chapter where Berger sketches these fruits is a suspension within a narrative of suspension, an interlude at his great French table, an invitation in from those who have found the way out. Shortly after finishing this book I was poking around a favorite Portland shop and came across a few pieces of ceramic fruit, painted the mottled colors of the vividly bruised, made by a neighbor of the shop owners, years before. I held the ceramic fruit in my palm, thinking about how artificiality is as real a presence in our lives as the food we eat, and also about Berger’s table set with fruit hardened from memory. I bought two peaches and thought to put them in a wooden bowl with a few real peaches, or apples or maybe even an avocado. They an altarpiece to memory and to taste, as one would remember the taste of a fruit long uneaten, or remember taste in general, in color and texture and emotion. I think sometimes we taste poems the way we taste food, or rather it is often the taste of a thing that’s most psychologically nourishing, in the same way our physical bodies need the whole table and the whole community around it to be satiated by the food on our plates.

Good Luck Charms

Good Luck Charms are reminders that thoughts and intentions have their object, and this we can define. Appointing charms is an act of creating definition and also of leaving room for the hoped for but as yet undefined good fortune. I wear a brass four-leaf clover and a tarnished whistle around my neck at times. The clover has “good luck” in various languages, phrases and sentiments pressed into its four leaves. I bought the piece with the intention to wear it until it’s time to give it away. I also have a silver, nondescript spoon that says “OK” on the length of its handle, lifted from an old hotel owned by a disowned prince, the palatial space once serving as backdrop to parties swirling with international socialites, actors, writers and the political elite on the Aegean coast of Turkey. “OK” is another version of saying “yes,” though with a thread of hesitancy, as if whatever you are saying “OK” to is not coming from yourself, but an assent to someone else’s idea. I don’t think you can pay for “yes,” it’s something that must either be discovered or simply taken for one’s own. The spoon as object is a vessel for transport, it is the embodiment of an in- between state, not meant to remain full for very long, nor to hold more than a mouthful, more than one can swallow. Holding more than one can swallow is an act I like to practice: matter in your mouth, matter poised in the spoon, thumb pressed against the OK… it’s in this process that the faiblesse of OK becomes the acuity of yes. It’s why we should hold more than we can chew, more than we can fit in our bodies. It’s a kind of cart-before-the-horse act in optimism, I guess, believing in the blue of a thing only blue at a vantage point of great distance. Agnes Martin says, “To try to understand is to court misunderstanding.” In seeking to hold what we don’t know how to hold, to understand that which we don’t know, we turn OK to yes and unspool whatever fate was knotted in our chest. Good luck charms come and go, and usually leave us at a time that feels too soon, at a time we don’t understand. But sometimes it’s important to leave the party first. I’ve written, “the one who leaves the party first leaves with the living prize” and I like to think, instead, that I’m the one who’s left the charm. The physical knows the physical; trust your body. It moves in and out and over and doesn’t lie about it.

Wind

Image credit: To Catch a Thief (1955)

I was in conversation with a former professor not long ago and, as he’s a sailor, talk turned to wind. He said when you reach a certain level of understanding around wind, you can actually see it. We thought about how wind is detected on all levels of sense—feel, temperature, scent, aurally, taste even—yet no one really talks about seeing the wind unless you are seeing the wind’s affect on an object. Though it’s argued you will begin to see wind once you know it well, on the sea specifically, and I wonder, when a phenomenon is so strong in all other areas of sense, how far of a leap is it for the final, missing sense to catch up with the others and interact with the phenomenon based on the framework the other senses have mapped and come to understand. It’s like any language, learning it is severely physical as you shed internal and external frameworks to take on another. It’s when all internal modes of understanding are working together—cultural, linguistic, philosophical, aesthetic, muscular—that you read a poem or imagine a response to a question without first translating the words. Otherwise, to translate without true understanding of the new language is to engage in a choreography of rearranging words into a more known framework. First, to understand their sound through ears steeped in a native language, then to formulate a final understanding or response not through the language you first encountered but through a language you are more comfortable with, a native language. Repeat the process backwards to respond. French to English, English to French, in my case. Without internalizing a new language, understanding ideas communicated in that language becomes problematic until it’s no longer new in your body. Each language carries with it a unique history, philosophy, and each idea presented in that language must first be understood in its original environment, that is, the environment of its native language. (Of course, misunderstanding is wonderful and valuable, too, in different ways). You don’t begin to truly see what’s being said in a language until you understand how that language functions inside of you and inside the body of a culture, a place (a kind of corpographesis). Just as you don’t begin to see wind until you understand how wind fundamentally affects your body and the bodies of all other physical things. This same professor, who translates poetry, likes to begin discussions on translation by quoting Frost: “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.” Yet one of the poets he translates, Abdallah Zrika, likes to counter him in saying: “Poetry is what gets found in translation.” Lost, found. Grief, presence, absence. The chaos of water in wind. The chaos of transformation. Peter Gizzi writes in the poem “Grey Sail,” “If I were a boat/ I would eat a sandwich."

The Agneses

Image credit: Les plages d'Agnès (2008)

When I think of the collective Agnes, I think first of mirrors. Each Agnes I’m preoccupied with, Varda and Martin, have something to say about mirrors. Varda says it visually in her autobiographical cinematic essay, Beaches of Agnes, when she sets mirrors on a beach and has them reflect the world around her, holds them in her hands and turns them slightly away from her face so we glimpse other people, other places. In an interview she mentions Gertrude Stein’s book title, The Autobiography of Everybody, and says about the mirror’s autobiographical reflection slightly trained away from her visage, “It’s me among other things.” Agnes Martin says, simply, in a discussion about art, “everything is a mirror.” And to bring in one non-Agnes, a Clarice whose perspective on mirrors is among the most beautiful, Lispector writes, “That crystallized void that has in itself enough space to go ever ceaselessly forward: for mirror is the deepest space that exists… A tiny piece of mirror is always the whole mirror.” My take on happiness of late, which has a certain ring to it, is this: it takes a Partner or a Platform. As in, one needs a partner or a platform, preferably both, weaving moments of intersection with moments of swerve. There is something profound lurking here, with these ideas of mirror and ideas of art and ideas of platforms. When I say platform I mean, in a sense, what art is for the artist, what numbers are for the mathematician, what vibration is for the vocalist. One’s mode of self-expression for the world and the self. In a partner, one’s mode of self-expression for the other and the self. And in both of these an exchange. A way to keep working. Of discovering our potential and moving toward its ever-shifting, shimmering form. To think of the mirror as a platform in itself, or a gateway to a platform, as icon of sorts for one’s art, is to believe it reflects the self, the other and the geography, yet that it’s also magical, a thing we must interpret. We see clearly but we cannot say clearly. The mirror can be terrifying, duplicitous, sometimes wily, not to be trusted. It’s powerful but it is only image, a beginning. My friend said once, there are times we look in the mirror and see ourselves older, younger. Just as there are times we look and see who we are in the present. To go into the mirror’s inherent darkness is to learn how to refract its light. The same way we learn a person, a place, a self. Agnes Martin again: “If we perceive ourselves in the work—not the work but ourselves when viewing the work then the work is important. If we can know our response, see in ourselves what we have received from a work, that is the way to understanding all truth and beauty.”

Color Is No Tourist: Saturational Concept

Image credit: Yves Klein

Yves Klein said “line is a tourist in the world of color.” Color is no tourist, color does not go on holiday. Line takes a tour through color’s vast insistence, makes arbitrary shapes or important statues and then keeps going. Color is not always fixed but it remains. What is line without its color? Klein’s journey into color involved an action: a jump off a mansard Parisian rooftop and into the void, which in his case was a quiet neighborhood street called Rue de l’Assomption. The Leap Into The Void was just a trace of the real piece of art; the original leap taken with no photographer present had Klein landing with his feet on the pavement dozens of meters below (his Judo training allowed him to make the leap mostly unhurt). He re-leapt again, twice, these times with a group below holding a net wherein he landed. This was the set-up for the photograph we see today, spliced with a photograph of the vacant street so as to evoke the original risk. He printed it in a newspaper of his own creation, the photo running front page, along with words more or less articulating his manifesto. “A man in space!” was the headline. Le Vide. The void is where our minds often take us, if we let them. Agnes Martin said: “The artist works by awareness of his own state of mind.” She also said: “There are two endless directions. In and out.” Imagine Klein’s shoes teetering on the ledge, perched just before the jump. The photo is his transaction, and looking at his arced body we see him in flight, our minds are held in the grace of the act, yet also in the rational fear of it. He is not falling yet he is falling. He is somewhere in between. On the spectrum between domesticated and wild, yet always untamed. Some gift, putting out into the wide air of the world. YK took his body where his gaze was, over the rooftop and past the ledge. He had an obsession with flying, truly believing he could learn to levitate, the way he heard monks had once learned to levitate. Thus, the imagined placement of his toes on that ledge, gathering the energy and concentration, all the practice and belief leading up to a leap, means a great deal in our hearts. An intake of breath, the heart stopping for an instant in darkness. Photographs are also photographs of a fixed heart, a caught heart, something stopped and held. Our hearts are held with Klein’s pointed toes, pinned to the French ledge and they are also held in the mid-air sequence. The color of jumping into the void is maybe not a color but a concept of saturation. A detail about Klein’s second show in Paris: he used enough blue dye in the cocktails to have everyone pissing in color for days.

Veronica Martin

Veronica's poems and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Kinfolk Magazine and Poor Claudia, among others. She lives in Portland, Oregon where she works for a creative firm and writes and curates a sometime column for Tin House's blog, The Open Bar, concerning the intersection of personal aesthetic and literature. She is at work on her first manuscript.